Part-writing Chords: Subdominant I

In the first Hub on part-writing we looked at the tonic and dominant chords and the usual ‘lines’ that realize the I-V-I chord progression, the concepts of chord ‘spacing’ and ‘doubling.’ In its companion, we learned about the vocal ranges for each of the four parts of the normal choral texture, and worked practice exercises to build skill in writing tonic and dominant chords.

If you’re not familiar with these materials, you should read those Hubs first (and most definitely work the exercises!) The links are given below.

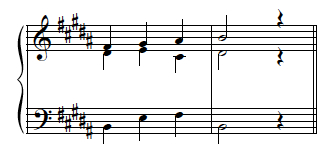

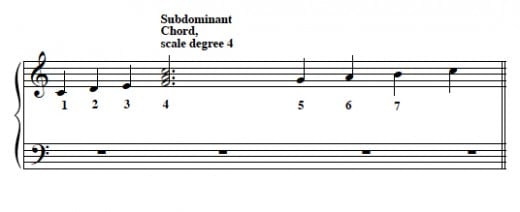

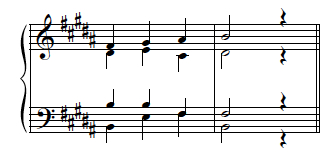

Assuming you are OK with all that, then in this Hub we’ll be looking at how to use the subdominant chord—that is, the chord built upon scale degree 4, as shown below. And as before, we’ll do that using a short chord progression as a model, and looking at the musical ‘lines’ making up that progression.

Previous Part-writing Hubs

- Part-writing Chords: Tonic And Dominant I

How to write the most common Classical chord progression, with audio/video examples and easy-to-understand explanations. - Part-Writing Chords: Tonic And Dominant I (Exercises)

A companion to "Part-Writing Chords: Tonic And Dominant I," this Hub consists of practical exercises to build skill in part-writing tonic and dominant chord connections.

Let’s start by contrasting the subdominant chord with the dominant. We’ve seen that the tonic and dominant are the two most important chords in traditional harmony: the dominant is the most unstable, ‘yearning’ chord, while the tonic is highly stable—the goal toward which the dominant yearns. Harmony is sometimes described as being “polarized” between these two extremes. In this context, the role of the subdominant is to prepare or lead up to the dominant.

(This description applies to what we might loosely call “the Classical style,” or more technically music from the “common-practice period.” Today’s popular music is not “polarized” in the same way: other chords than tonic and dominant can take important roles in the harmony, and the succession of chords can accordingly be freer. For example, in Classical style, the subdominant almost never follows the dominant, and rarely begins a phrase; in contemporary popular harmony, neither of these is unusual. In this series of Hubs we are studying Classical practice.)

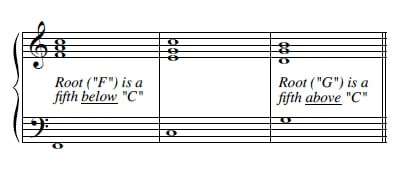

From another point of view, the subdominant is quite similar to the dominant, in that the roots of both are a fifth away from that of the tonic chord, as shown for the key of C major in Example 2 below.

The root of the dominant is a fifth above that of the tonic, "C"; the subdominant’s, a fifth below.

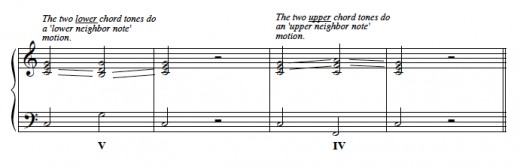

That means that the voice-leading needed for I-IV-I progressions are the inverse of those we’ve already learned for I-V-I progressions. In a way, I-IV-I is I-V-I turned upside down. Here’s an illustration of how that works:

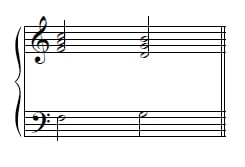

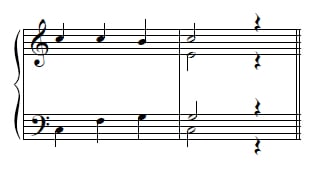

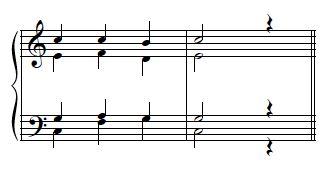

The version of I-V-I seen in Example 3 combines neighbor-note lines—the “1-7-1” and “3-2-3” lines in the lower two notes of the treble staff—with a “common-tone” line, “5-5-5,” which simply holds the one tone common to both chords. Correspondingly, the subdominant equivalent has “5-6-5” and “3-4-3” neighbor tone lines above a “1-1-1” common-tone line.

Actually, the voice leading of all pairs of chords with roots related by fifth can work similarly—though as we’ll see later, the chord upon scale degree seven has some limitations that will affect this statement. So, for example, ii-vi-ii, or vi-iii-vi could use voice leading (another term roughly synonymous with ‘part-writing’) corresponding to that illustrated above. The term used for this is “root motion by fifth”—or by fourth, as it works out to be the same thing for practical purposes.

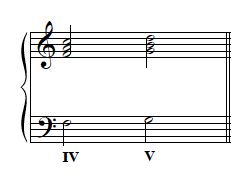

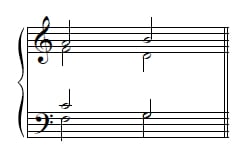

However, the subdominant’s relation to the dominant in part-writing is very different. The roots of IV and V are a second apart, and the ‘math’ of the chords works out in such a way that there are no chord tones in common at all, as shown:

In popular music, connecting the two chords just exactly as they are shown above is a pretty common thing. Not so in common-practice music. In the latter style, the voices which comprise a harmony are intended always to maintain their independence, and the harmonies are to blend smoothly and (normally!) to succeed one another smoothly. Musicians discovered early on that allowing certain types of parallel motion disrupted that goal.

Specifically, if two parts separated at the intervals of the perfect octave, perfect unison, or perfect fifth move in parallel, they tend to lose their independence due to the ‘unifying’ quality of those intervals. This also can be heard as a sort of disruption of the harmonic texture. Listen to the different impact of the same melody, set in parallel motion at three different intervals:

So, we have a new rule: in common-practice part-writing, parallel octaves, unisons and fifths are to be avoided, with very few exceptions ever allowed.

It’s when we’re writing progressions using root motion by second that these types of parallels are the most tempting. In practice, though, what might seem almost intimidating actually makes things easier, since avoiding faulty parallel motion really reduces the options to just one common voice leading. It’s shown below:

This version is easily summed up: the bass moves up by step, while all other parts move downward in contrary motion. In the upper voices, that gives us a “1-7” line, a “6-5” line, and a “4-2” line—that last moving down by skip instead of step. Of course, the upper voice lines can be presented in any vertical order in realizations of this progression, and all the lines are pretty common in the soprano, including the “4-2” line.

Although this is the normal IV-V pattern, there is at least one variant you might run into. It makes careful use of parallel thirds between bass and (in this case) soprano parts:

It’s much less common, perhaps because the leap of a fourth, seen above in the tenor voice--“C” down to “G”—makes it less smooth. However, it’s clearly a ‘legal’ option.

Just as was true for chord progressions using root motion by fifth, any two chords with roots related by second can use the same voice-leading patterns laid out here--for example, a V-vi progression, or even the time-reversed vi-V. But as we’ll see in a later Hub, not all such progressions work as well, or are used as frequently, as IV-V.

Exercise 1

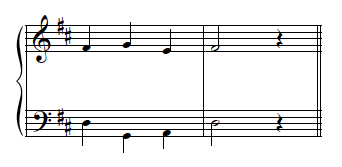

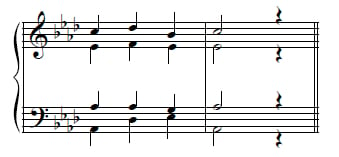

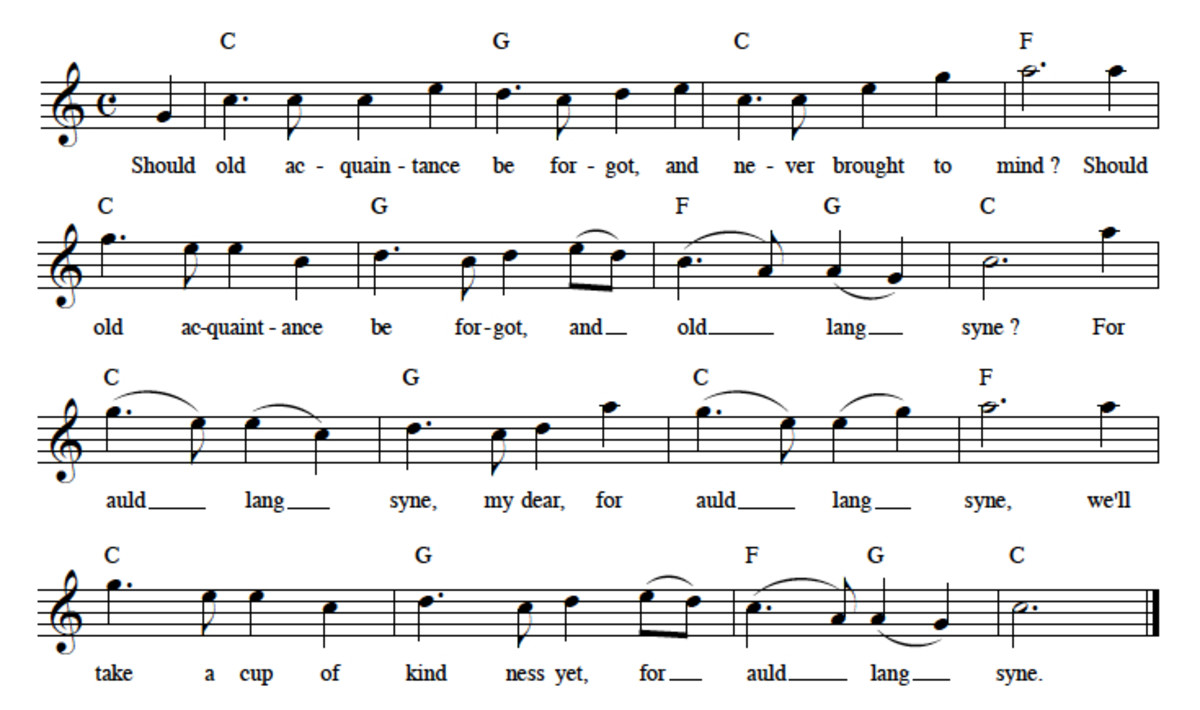

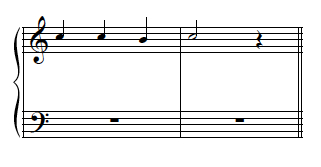

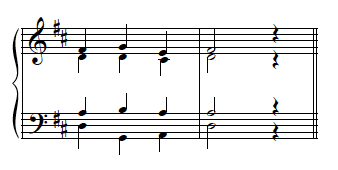

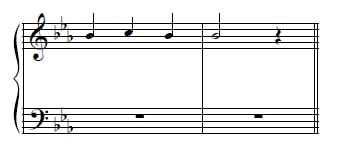

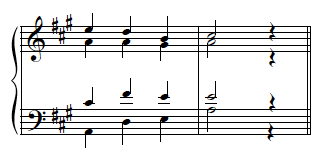

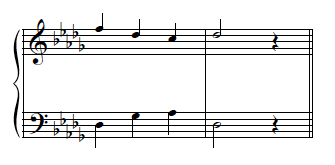

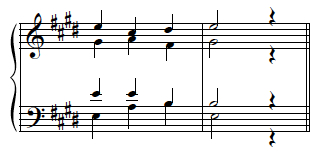

Now let’s practice using these voice-leading patterns in different keys, using the 4-chord harmonic pattern I-IV-V-I. We’ll walk through the first one as an example. Here’s the given soprano line, to be harmonized with the pattern I-IV-V-I. As a review question, what key are we in? And what scale degrees form the soprano line?

No sharps or flats makes the key C major—jokingly referred to sometimes as “the people’s key”—and the soprano line is “1-1-7-1.” Your first step should be to write the bass line corresponding to the roots of the I, IV, V and I chords.

(Yes, physically write—it will help engrave these patterns in your mind. Manuscript paper can be downloaded for printing at home at the link below . I strongly recommend you print some out and actually write down the question--and your answers! This information will stick with you a lot better if you do.)

Manuscript Paper Link

- Grand Staff Templates | Free Blank Sheet Music

Free blank grand staff templates in portrait and landscape orientation in PDF format.

Here’s the best bass line. It’s not the only correct version; you can shift the octaves around a bit without causing trouble. But don’t:

- Write the “C” below the bass staff—it’s below the usual vocal range; or

- Write the “F” and “G” in different octaves—the bass must approach the “G” by step, not by the awkward leap of a 7th or 9th.

But how do we add the next notes? We don’t yet know the characteristic lines that we can use for this progression.

Let’s approach this question more ‘vertically’ then, one chord at a time. Let’s start by picking a well-spaced chord that we want to end on, like this:

In this version, we have arbitrarily chosen to write the chord in what is called ‘open spacing.’ That means that the upper voices have potential chord tones ‘separating’ them—for instance, the alto could have had the “G” lying between the “E” and the soprano “C”, rather than the actual “E” written, since that “G” is a chord tone.

Similarly, the tenor could have had a high “E.” Had we written the chord that way, then all the chord tones in upper voices would have been ones immediately adjacent to each other. Logically enough, a chord whose voices occupy adjacent chord tones is said to be in “close spacing.” The close-spaced version of this particular chord would look like this:

With a chord to aim toward, we can now use the patterns we know for the connection of the V-I chord. Look back to Example 10, and see if you can pick the correct chord tones needed to make the V chord connect smoothly with the I.

As shown, the tenor “G” is the tone common to both chords, giving us a “5-5” tenor, while the alto runs parallel to the soprano, “2-3.” Use the contrary motion pattern for IV-V, which we discussed above, to fill in the IV chord.

The tenor has “6-5”, parallel to the soprano, while the alto skips downward, “4-2.” Now fill in the first chord to complete the exercise.

The common-tone line is already given in the soprano (“1-1”), so the neighbor notes must come in the inner voices. The alto has “3-4”, while the tenor gives us “5-6.”

Let’s shift our focus to the entire lines now: the alto line is “3-4-2-3” and the tenor is “5-6-5-5”; they accompany a (mostly) common-tone soprano tracing “1-1-7-1.” Let’s use these lines as the patterns for our next several exercises, which simply move the progression from key to key, and the lines from voice to voice.

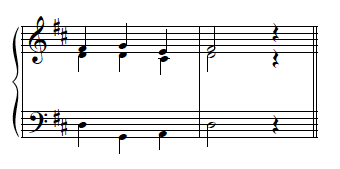

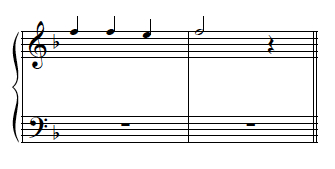

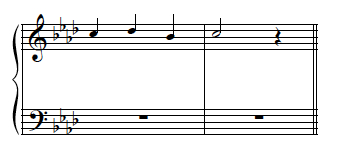

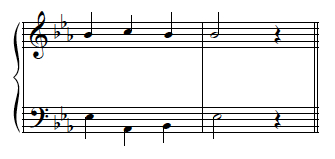

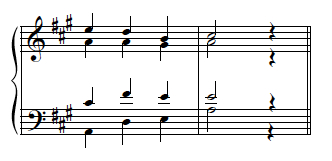

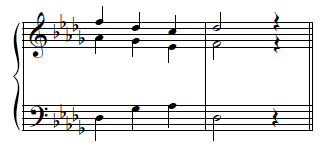

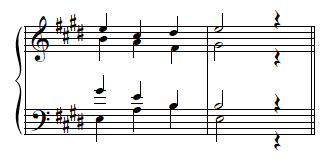

Exercise 2

As in previous exercises, first identify the key.

(As a reminder, there are two simple rules that let you find the key from the key signature; they are given just below in case you have gotten a bit foggy on the details.)

Reminder:

1) For keys with flats in the key signature: the last flat to the right is always scale degree 4; to find the tonic, count down the scale to scale degree 1. Shortcut: for all keys with 2 or more flats in the signature, this will also work out to be the 2nd last flat in the key signature.

2) For sharp keys, the last sharp is always scale degree 7; to find the tonic, go up one scale step to scale degree 1.

When you've got the key, identify the scale degrees of the given line.

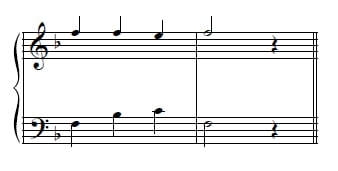

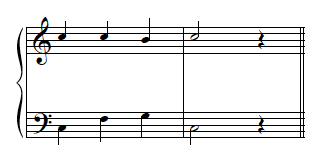

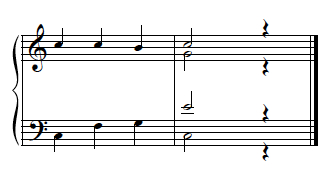

We are in the key of F, and the soprano corresponds to that of exercise—“1-1-7-1.” Add the bass line next, then the line beginning on scale degree 5. Finally, add the line beginning on scale degree 3.

This harmonization is identical to that of exercise 1, and there’s not much alternative in this key—other possibilities create too much space, or else take the tenor too high. Let’s try another.

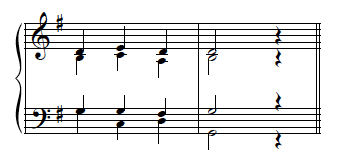

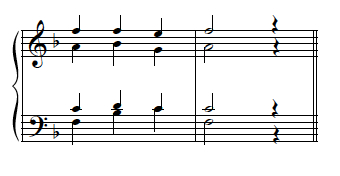

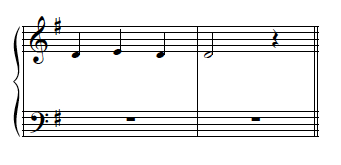

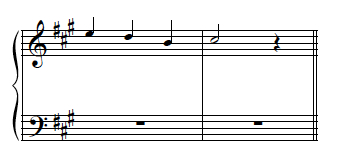

Exercise 3

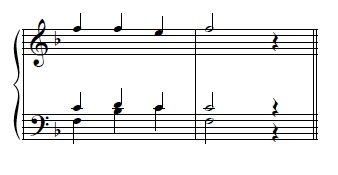

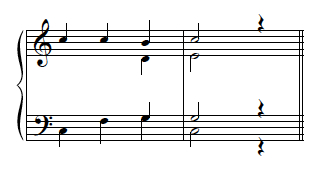

As always, start by identifying key and the scale degrees of the soprano line given.

D major, “3-4-2-3.” Add the bass, then alto and tenor, in that order. Once again, there’s really only one solution.

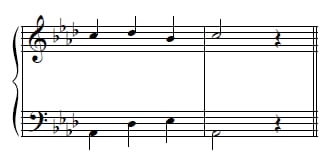

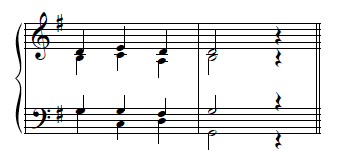

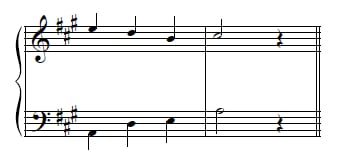

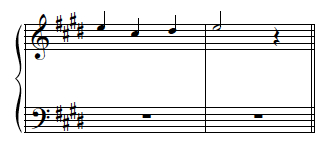

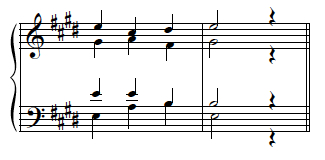

Exercise 4

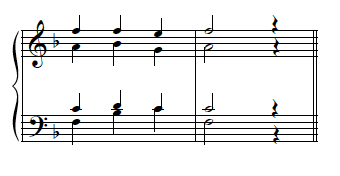

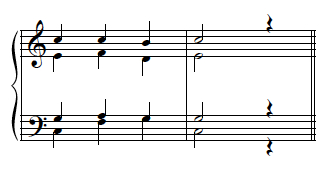

Key and soprano scale degrees?

Add a bass, beginning on the "Ab" at the bottom of the staff. Then add alto and tenor in that order.

As a quick review question, is your first chord in ‘open position’ or ‘close position?’

(A reminder of the definitions of these terms is given just below.)

Reminder:

1) Close position chords have upper voices which occupy adjacent chord tones—in other words, their tones are as close together as possible.

2) Open position chords have upper voices separated by an ‘unused’ chord tone—their tones are spaced farther apart.

This is open spacing all the way.

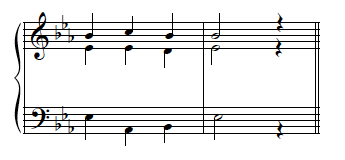

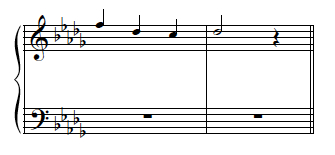

Exercise 5

Let's do a couple more similar exercises for practice before we change it up slightly.

Key and soprano scale degrees?

It’s a “5-6-5-5” line, in G. Add a bass line, but this time begin on the upper “G” in the bass register and end on the lower “G.”

Does this combination of bass and soprano change something about the spacing of your first chord? Ponder that question as you add alto and tenor parts.

Yes, with the bass and soprano so close together you are forced to use close spacing--there's no room between soprano and bass to spread out the inner voices.

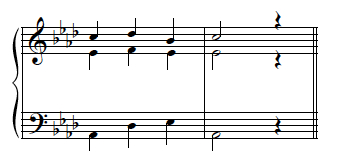

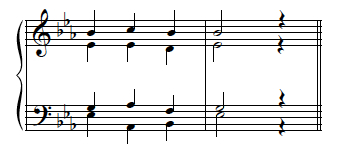

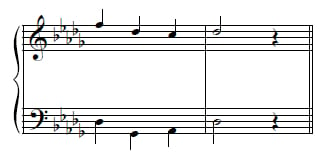

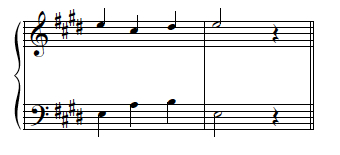

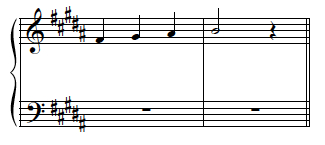

Exercise 6

Key and soprano degrees?

Once again, we have a “5-6-5-5” line, this time in Eb major. Add a bass line, and include the lower “Bb” in the bass register.

This is the only solution with the low "Bb"—the low "Bb" requires the low "Ab" as well, since you don’t make wide jumps between the roots of the IV and V chords. And the low "Eb" is too low for our ‘legal’ bass range. (Though that doesn’t mean it’s never written for basses in the ‘real world!’ But it is uncomfortably—and therefore dangerously—low for an average bass section, which is why it’s ‘illegal’ for our purposes.)

Can you use open spaced chords? If yes, do so as you add alto and tenor parts.

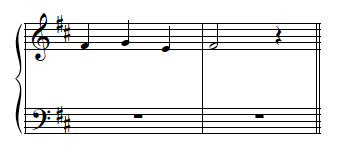

Exercise 7

Let’s try a different given line. What are the key and scale degrees?

“5-4-2-3,” in A major. How can we adapt our lines to deal with this change? Ponder how to do that as you add the bass line—start the bass line with the low “A” and end it with the high “A.”

Here’s the bass.

A good strategy for approaching the new soprano is to compare it to the lines we used previously. Clearly, “5-4-2-3” is most similar to “3-4-2-3;” only the first tone differs. So let’s look back to Example 18, which uses that line—for convenience I’ve presented it again below, transposed to our present key.

Using that model, complete alto and tenor.

Note how the voice exchange forces the leap of a fourth in the tenor, so that it initially moves in parallel tenths with the bass. (A tenth is the same as an octave plus a third.) This also helps make the switch from the open-spaced I chord to the close-spaced IV.

Exercise 8

Now try this soprano:

This soprano—"3-1-7-1" in Db—has the potential to create a problem which we haven’t so far discussed: the tricky beast known as the ‘similar fifth.’ Unlike parallel fifths, which are ‘illegal’ when they occur between any pair of voices, similar fifths only create a problem under a specific set of circumstances. Here’s the rule:

When bass and soprano to a perfect fifth in similar motion, and the soprano does not move by step—that is, when it moves a third or more—then a prohibited similar fifth has occurred.

The musical effect is similar to that of a parallel fifth, and—as with parallel intervals—can occur in the case of octaves as well as fifths. Here’s how it would look in the case of Exercise 8:

Consider the motion from the first 'chord' to the second: since the soprano and bass both move downward, but not by the same interval, they are moving by similar motion—and the soprano (which skips down a third) is moving by skip, not step. These are precisely the two conditions described above as creating an illegal similar fifth!

Luckily, the cure is easy. Simply take the bass upward to the “Gb,” creating contrary motion instead of similar, as shown below:

Now add the alto part.

Add the tenor. Hint: it is almost, but not quite, in correspondence with the “5-6-5-5” line we’ve used in several instances; only the first tone differs.

Notice that this alto line, “5-4-2-3,” corresponds to the soprano line we just used in Exercise 7. Does the tenor line correspond to a previous line, too?

Exercise 9

Key and scale degrees?

In E, we have a “1-6-7-1” soprano. Note what’s ‘dangerous’ about this line: we can’t use the normal option of moving the upper voices contrary to the bass when connecting IV and V, since the given soprano is in parallel thirds with the bass. Parallel thirds are good, but since we know that this scenario is not quite normal, let’s proceed with caution!

There are several other good options for the bass, including writing it an octave lower. These would affect the ‘sound’ of the harmonization a bit, but shouldn’t affect the part-writing.

This comes close to passing muster, although the tenor is a semi-tone above our ‘legal’ range, and also moves with a consecutive skip and leap. To eliminate these flaws, we can use another new option: that of writing an incomplete chord.

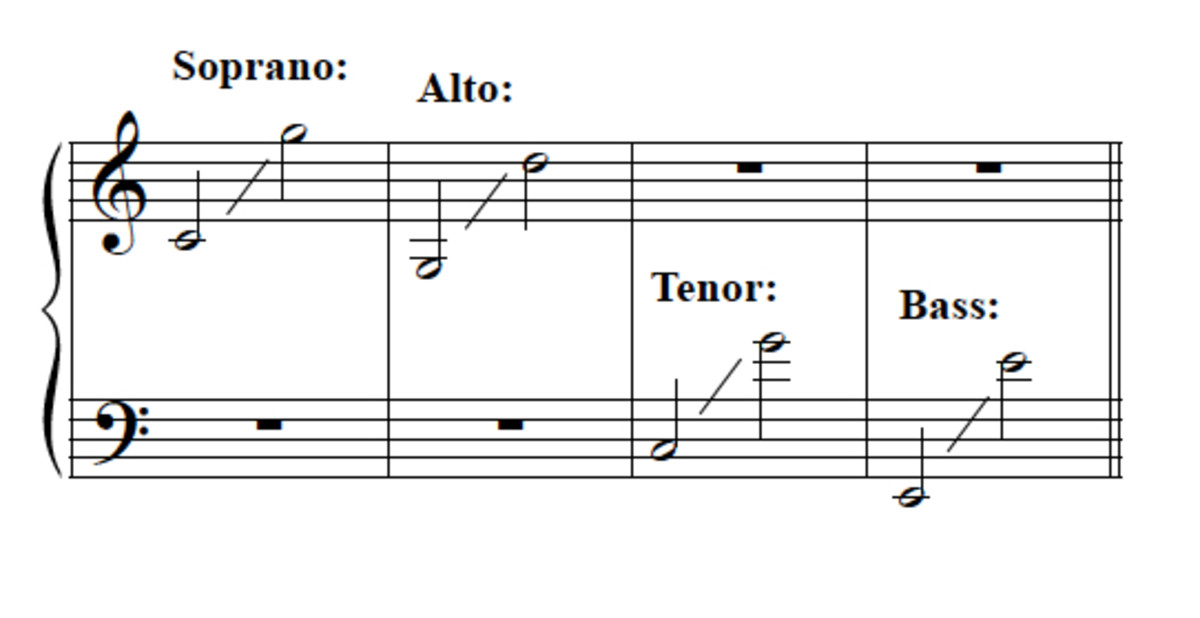

So far, all our chords have been "complete"–that is, they contain all three chord member: a root, a third and a fifth. However, in common-practice style it can sometimes be advantageous to omit the fifth of a triad, leaving only root and third. (Note that the fifth is the only member of a triad which may be omitted! Triads must have both root and third in common-practice music.) So our doubling options include the use of incomplete triads.

Here’s how it works in this example:

The tenor’s “E” is much more comfortable in terms of range, and now acts as a common tone to the following subdominant chord. The alto must provide the third of the chord, since the tenor no longer does. The chord now consists of a tripled root plus a third. This may seem strange or unbalanced, but in fact it works very well, and is quite a common voicing in the ‘real world.’

The alternative would be to double both root and third; this, too, happens sometimes, but less often than the triple root. Note that it never happens with the dominant chord, since the third of the dominant is the leading tone—too active a tone ever to double.

Here's a video example with both versions:

The common tone version is preferable, but most listeners will have to work hard to hear the difference. (On the other hand, the difference will be very noticeable to many tenors!)

Exercise 10

Let’s try something similar.

We have “5-6-7-1” in B major. Clearly we won’t be using an incomplete tonic triad to start, since the fifth is already included in the given soprano. Does this affect the other parts? Complete them to find out.

No, as it turns out. The alto and tenor correspond exactly with those used in Example 38. The difference is only the complete triad resulting from the fifth given in the soprano.

Doc Snow on Wordpress!

- snowonmusic | A music theory blog that's NOT all work!

Ask the Doc questions, hang out, or play musical parlor games like "What Would Johann Do?"

Summary

Well, that is surely enough brain work for one session. To recap a bit, we’ve looked at the following points:

- The function of IV in common-practice harmony, namely, preparation of the dominant;

- The similarity of IV to V in terms of its part-writing in connection with the tonic chord, namely that it can be written rather like an ‘upside-down’ dominant chord;

- The avoidance of parallel perfect fifths, octaves (and unisons) in common-practice harmony;

- Normal and alternate voice-leading patterns for connecting IV and V chords;

- The avoidance of similar fifths and octaves between soprano and bass in common-practice harmony;

- The use of incomplete triads.

Once again, we’ve covered lots of ground—certainly lots for just one Hub. But stay tuned—there’s more yet to come as we continue this series!

Other Hubs by Doc Snow

- Part-writing Chords: Summary I

A 'syllabus' and summary for Doc Snow's innovative Hubs on the essential musical skill of part-writing. Sequence, content and links--plus a summary of part-writing 'rules.' - Part-writing Inverted Chords: Primary Triads In First Inversion

How to use inverted triads in common-practice four-part writing. Learn to write tonic, dominant and subdominant in first inversion--these explanations, illustrations, and practice examples make it easy! - How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently, Part One

The first of a pair of articles on how (not) to practice music, this article sets the record straight on much confusing practice advice you hear. Plus, great pictures of some musical greats! - Understand Chords: Beyond Seventh Chords To Chord Extensions--Ninths, Elevenths And Thirteenths (Pa

Extended chords-ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths-are undoubtedly hipper than the average triad. But what are they, how do you use them, and, most of all, what do they actually *sound* like? The text and video of this guide to extended chord basic