Part-writing Inverted Chords: Second-Inversion Patterns II--Passing & Cadential

This Hub is the second of two discussing the voice-leading patterns one must use in writing second-inversion triads; the first is linked in the sidebar below the picture and to the right, in case you wish consult it before working through this one.

A site offering free manuscript paper downloads is linked as well; "working through" this Hub isn't just a figure of speech. For best results, the practice questions given below should be worked through on paper before clicking through to see the answers. (Those answers 'appear' one voice at a time, by the way.)

Or you may wish to check out still earlier part-writing Hubs. There are quite a few, and there is a recommended sequence in which to work them. You can see a summary of the first series--it deals with part-writing root position triads---in the sidebar as well; it should help you find the best place for you to start. A similar summary for this series--part-writing inverted triads--will be coming soon.

- Part-writing Inverted Chords: Second-Inversion Patt...

Part-writing second-inversion triads is paradoxically both easier and more 'dangerous' than root-position or first-inversion triads. Find out why here--and learn to navigate the tricks and traps with video examples and interactive practice questions! - Free printable staff paper @ Blank Sheet Music .net

- Part-writing Chords: Summary I

A 'syllabus' and summary for Doc Snow's innovative Hubs on the essential musical skill of part-writing. Sequence, content and links--plus a summary of part-writing 'rules.'

If you are reading this paragraph, presumably you've decided that right now, this Hub is the one for you. That would imply that you are already familiar with the more straightforward types of sic-four chords we dealt with in Second-Inversion Patterns I: the Alternating/Arpeggio six-fours, and the Neighbor Six-four.

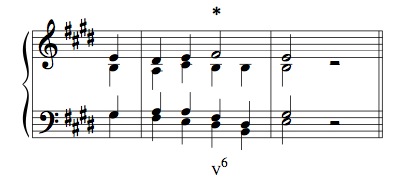

In this Hub, we'll explain--and practice!--the very common and useful Passing Six-four, as well as the Cadential Six-four which suggested the signature photo, above. As with the previous Six-four chords, the acceptable ways of using these chords are quite specific. Second-inversion triads cannot be used at random--not, at least, if you wish to stay within the bounds of Classical (or "Common Practice") musical style.

Let's begin with the Passing Six-four.

Passing Six-fours

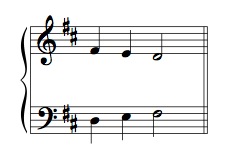

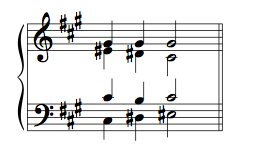

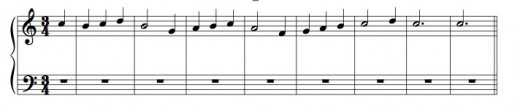

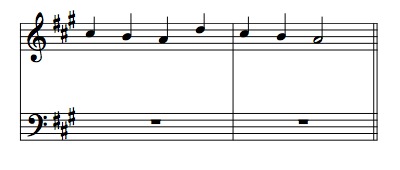

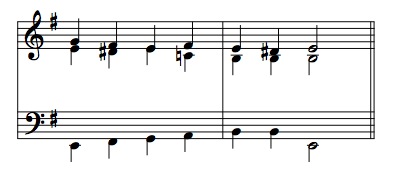

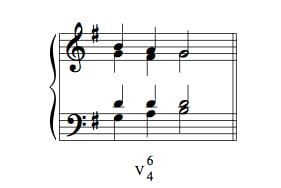

In neighbor six-four chords, we saw conjunct motion similar in contour to the pattern formed by actual neighbor (auxiliary) tones. Occurring in two voices, it created a different chordal sonority prolonging a primary harmonic function. Passing six-four chords are somewhat similar, in that they prolong nother chord by linear motion. The 'passing tone' motion occurs in the bass, as shown below:

Notice, however, that not all voices follow a passing-tone motion. Although one voice--the soprano in this example--moves precisely contrary to the bass, another keeps the common tone, while the remaining voice executes a neighboring pattern!

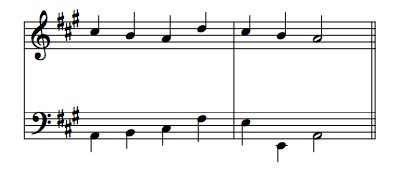

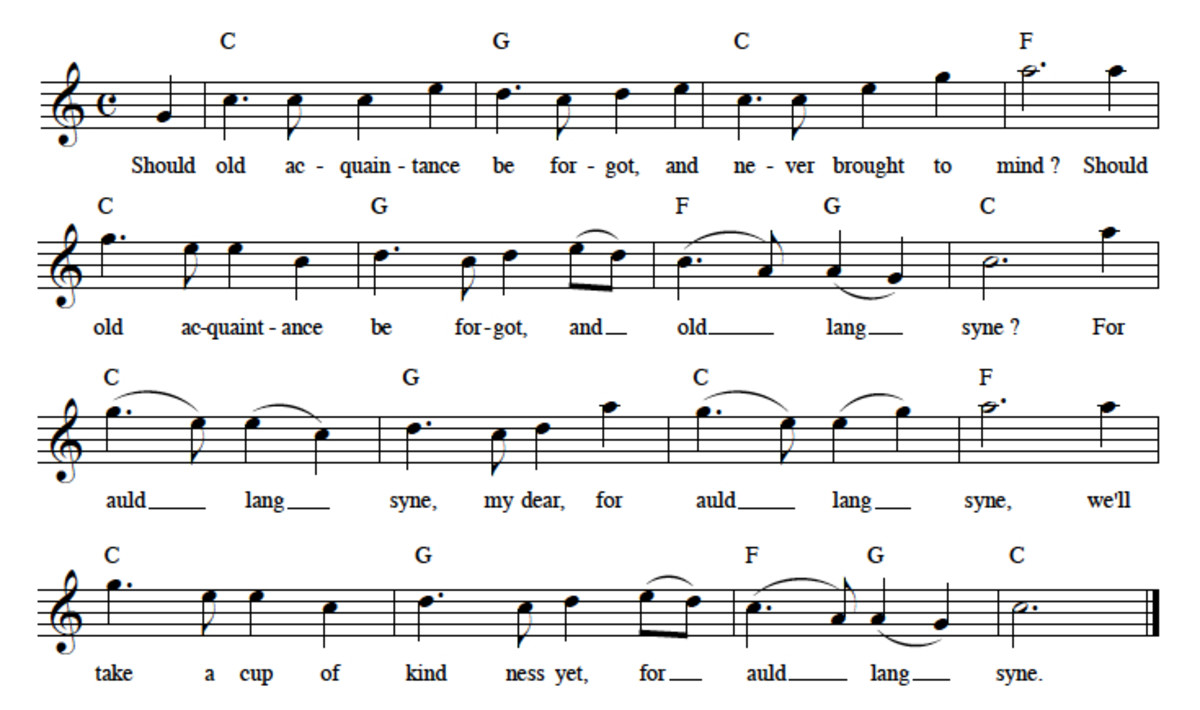

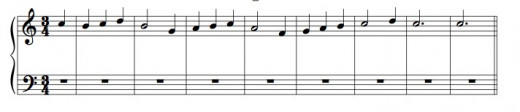

Try a couple of quick practice questions. First, this snippet of melody:

And in minor:

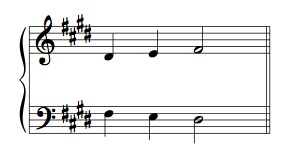

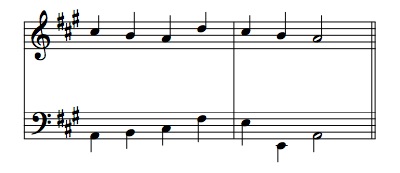

The passing six-four usage we've worked on so far--in which a dominant in second inversion links tonic triads in root position and first inversion, forming a prolongation of the tonic harmony--is undoubtedly the single most common. However, the voice-leading can be applied to prolong other triads, too. The most prominent of these would be the dominant:

Note that this example differs from Example 1 by a single tone: the F# becomes an F natural. This is enough to provide an unambiguous tonal context to our ears, however; we may not be able to identify or articulate the sound verbally, but we know which sorts of chords are apt to follow it.

(By the way, if this example sounded 'wrong' to you, it was probably because you were hearing it out of context: it is easy to expect the first chord to be a tonic triad--and if you make this intuitive assumption, the lowered seventh (the "F natural", in this example) will tend to sound like a wrong note.)

Try writing a similar prolongation of the dominant using a passing supertonic six-four to harmonize the soprano below. But think carefully about the key and its implications! This question has a built in 'trap' to avoid.

The key must be F# minor, since the soprano line would not fit the prescribed harmonies in A major. Therefore, the bass should start on C#, the dominant scale degree, and move upwards. But we want it to end on the leading tone, E#, not the subtonic, E natural, since the point here is to prolong the dominant harmonic function. That in turn implies the use of the raised form of the sixth scale degree, D#, since we would not wish to create the melodic augmented second (D natural to E#.)

In other words, we need to use the melodic minor scale, not the harmonic minor. Of course, this also creates a minor triad on the supertonic, not a diminished one.

This voice leading pattern may also be seen and heard 'in reverse.' Try a practice question prolonging the dominant with a supertonic six-four, but starting with the first-inversion dominant instead of the root position this time:

This is interesting! Here we are forced to use not just the melodic minor to form our chords, but the 'wrong' form of it! That is, this descending line features the 'ascending' form of the melodic minor scale.

But the seeming paradox is a necessity--if we used the tones of the descending form of the melodic minor, we would lose the dominant harmonic function. (Of course, there could be musical contexts in which we wished to do just that for one musical reason or another.) In that case, the voice-leading would be quite similar, but the tones of the descending melodic minor would be used.

Other prolongations are also possible. In normal tonal music they are seen much less frequently, since normal harmonies 'polarized' around tonic and dominant functions. One possibility is to prolong the leading tone triad. Try doing so, using the following soprano. What passing passing six-four is needed?

As shown, the passing chord works out to be IV 6/4, and the chord prolonged is the leading tone triad, viio. The voice-leading patterns of the inner voices are different from what we have seen before because we are following normal doubling practice.

(As discussed in previous Hubs, our guideline is that the primary tones in the key--scale degrees 1, 4, and 5, with 2 following--should be the ones doubled. The leading tone, by contrast, is almost never doubled. The need to avoid that doubled leading tone is an important factor in arriving at the voice leading shown.)

If the sound of Question 5 seems harsh, hear it again in the context of a progression that prepares it and resolves it:

Part of the harshness comes from breaking one of our 'rules': one doesn't usually write the leading tone triad in root position. (The same applies to the diminished supertonic triad sometimes found in minor mode.) In the present context, though, the preparation of the dissonant root position by the first inversion, and then followed by the harmonically stronger root position dominant, goes a long way toward justifying the dissonance to our ears.

(By the way, the voice-leading in the tenor is worth remarking upon as well: the leap of an ascending fourth from leading tone to mediant is a fairly frequent option when there is no more elegant way to include the third of the tonic. The voice overlap with the bass in this example is also not uncommon.)

The overall effect of the first complete measure is of a single prolonged dominant harmony--the leading tone triad's function is dominant in any case, and the final dominant triad in the measure comes as a summation of the harmonic meaning of the preceding triads.

Still, it is easy to suspect that many composers would prefer a slightly different version:

Here, the root position leading tone triad is replaced by a first inversion dominant triad. Only a single tone changes, but much of the remaining harshness disappears: we have no root position diminished triad, and the voice leading in the alto is simplified and strengthened.

Here we have an example in which the passing six-four connects two different triads, albeit ones expressing the same basic harmonic function. (That is, viio and V are different triads, but both express a dominant harmonic function.) This could occur in other harmonic contexts, too, by connecting other pairs of third-related triads via a passing six-four.

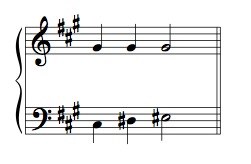

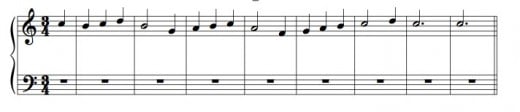

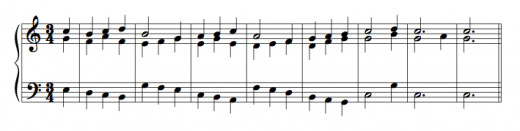

To conclude our section on the passing six-four, let's do a 'grand finale,' in which a succession of passing six-four prolongations creates an expanded harmonic progression. Each measure should contain a different 'six-four prolongation' using a Passing Six-Four chord. (Of course, this will mean that the half notes will have to be harmonized with two chords, so the lower voices will move in a different rhythm in those measures, in a manner somewhat similar to that of Examples 3 and 3a.)

It's easy to see soprano lines similar to the soprano of Example 3 and 3a--for example, measures 1 and 3. But is there another line, somewhere in the texture of Example 3 or 3a, like the question's soprano in measures 2 or 4?

Using Example 3 as a model, try to create a bass line fitting the hints just given.

As shown, prolongations of viio, iii, vi, ii and V can be created. There is also a 'bonus' repetition of the cadential V-I, followed by a repeated tonic. These extend the phrase structure to a 'balanced' eight measures. The repetition is a good opportunity to make use of the 'neighbor six-four' as well, as indicated by the figured bass numerals shown.

In general in a harmonic sequence--that is, a sequence in which systematic transpositions of all four voices determine the harmonic structure--the details of the voicings remain constant throughout, even where this implies such normally forbidden procedures as doubled leading tones. However, here it is convenient to modify the voice leading a bit, beginning in the fourth complete measure to set up the cadence.

Try writing the inner voices according to the hints just given.

A rather synthetic, but not unmusical invention!--though no-one will mistake it for great art.

Let's move on to our final second inversion idiom.

Cadential Six-fours

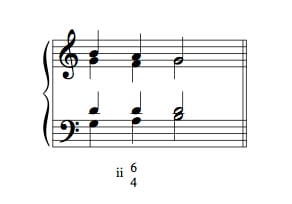

One very common six-four occurs at cadences. Logically enough, it receives its name from its location. (For those unfamiliar with the term, a 'cadence' is a stereotyped harmonic/melodic formula used to articulate phrase endings in 'Common Practice' music--or sometimes musical gestures which work in a similar fashion to such formulae. But a real discussion of 'cadence' goes beyond the scope of this Hub.)

In one way, the cadential six-four is unique: so far six-four chords have appeared upon weak beats in the measure, thus softening the dissonance. By contrast, in the cadential six-four the dissonance is emphasized by placement on an accented beat (most often beat one.)

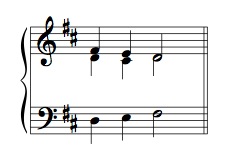

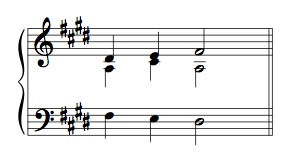

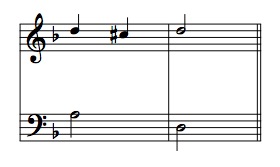

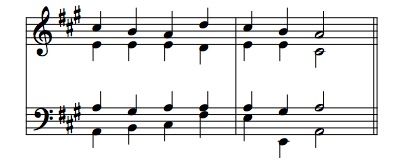

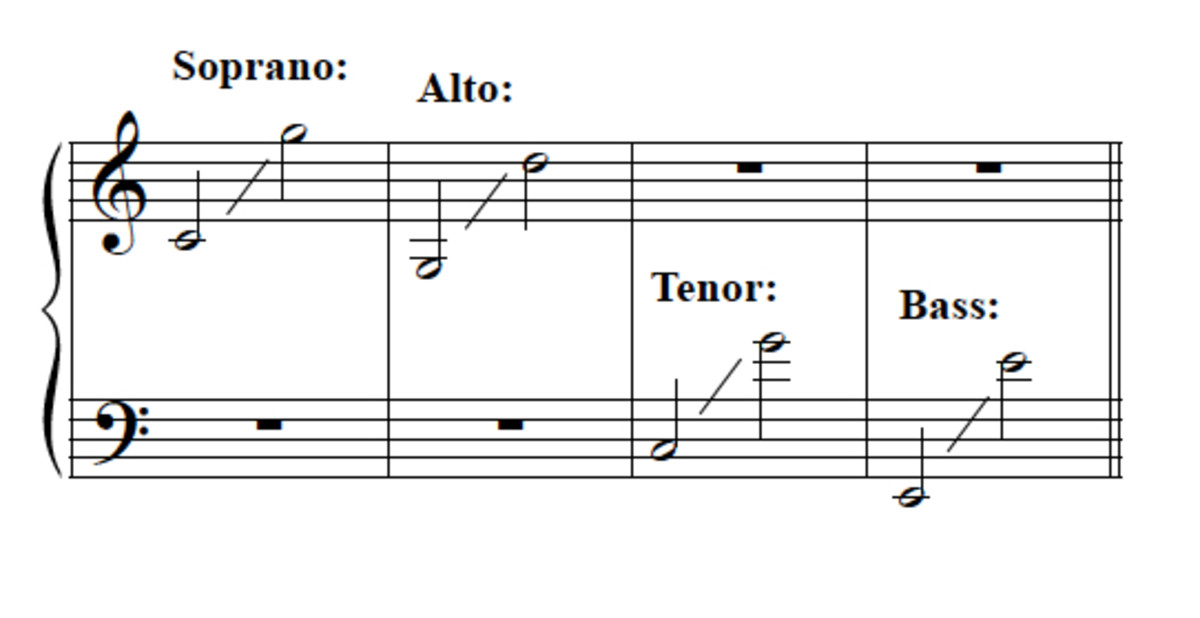

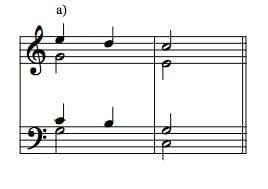

Resolution is just as in the neighbour six-four, however: over a static bass tone, the upper voices fall stepwise. Example 4a illustrates.

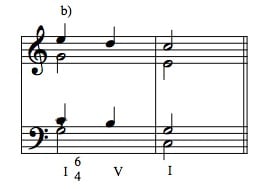

By the way, there is are two schools of thought about how to use Roman numerals to symbolize this chord. The 'Old School' considered the cadential six-four from the 'vertical' perspective so natural to the methods of figured bass, and find a second-inversion triad rooted upon the tonic. (Implicitly, that is also the logic underlying the inclusion of the cadential six-fur in this Hub!) Therefore, the chord symbol I is used, as shown:

This idea was emphasized by one traditional terminology which labeled this usage a 'cadential tonic six-four,'--logical enough, if redundant. (The cadential six-four only occurs in this harmonic context: unlike the other six-fours, it does not occur transposed to other scale degrees. So there is no 'non-tonic cadential six-four chord.')

Or is there?

More recently, music theorists influenced by the work of Austrian theorist Heinrich Schenker have correctly pointed out that this chord is really not so independent: the apparent two chords of the idiom, the tonic six-four and the dominant, really constitute a single dominant which is embellished by a linearly-conceived dissonance. To put it another way, the first of the 'two chords' is really not an independent chord at all, but an appoggiatura--a type of non-chord tone found in accented metric positions, and resolving downward by step.

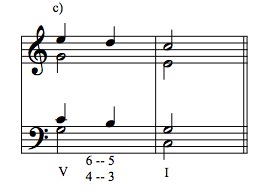

From this perspective, it would be logical to suppress the "I", since there is no tonic function involved. So perhaps this chord should be called the "dominant cadential six-four chord?" At any rate, in the harmonic labeling of this progression, a single "V" is used to indicate the dominant function. Figured bass numerals indicate the voice leading:

This more recent analytic view seems to be gaining the upper hand over the more traditional 'vertical' view. However, the part-writing remains the same, only the Roman numeral analysis (and the conceptual framing underlying it) differ.

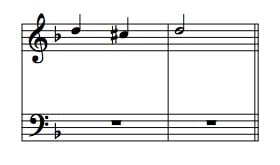

Let's practice writing the cadential six-four in several different keys. The first may challenge you a bit! Identify the key as usual, and add an appropriate bass, using Example 4 as a guide.

As shown, the key is D minor--the C# is the leading tone, and a very broad hint to the minor key! In Example 4 there is no 1-7-1 line, but you should have no great trouble using our by now long-familiar tactic of exchanging chord tones among voices to understand how such a line can exist within the context of the cadential six-four.

Add the appropriate inner voices to your soprano-bass outline, beginning with an open position chord.

The alto falls naturally into parallel sixths with the soprano, while the tenor doubles the bass tone--doubling the bass of a cadential six-four is an almost invariable practice. The result is a 3-2-3 line.

A figure frequently seen with the cadential six-four is a bass line leap (or drop!) of an octave. Here it is, in the context of Question 7:

Try using the 'octave drop' figure in this six-four (add all remaining parts):

Did you remember the raised leading tone?

Theoretically, one could write the cadential six-four with the 5-5-3 line as soprano. But there's not normally much point in that; the cadential six-four tends to be used at relatively strong cadences, where the melody would generally cadence to tonic. So the two common possibilities for the soprano line of a cadential six-four are 1-7-1 and 3-2-1. (1-2-1 is out, since the tones of the cadential six-four do not rise, as the 1-2 does.)

Try harmonizing the melody below, using both a passing and a cadential six-four. Write the bass line first.

The cadential six-four figure occupies the second measure completely, leaving just four chords to accommodate the passing six-four. The latter pattern must begin either on beat one or two, then, and we know that the second chord--the dissonant six-four--must be on the unaccented beat. Therefore, the passing six-four figure must begin on the first beat of measure one.

Now add the inner voices.

One could also harmonize beat 4 with a root-position subdominant:

The technically squeamish might shrink from this version, because the usual definition of the part-writing error called "similar octaves" describes this progression exactly: the octave between bass and soprano is reached by similar motion, and the soprano leaps to reach it. Yet the stepwise motion in the bass and the indirect yet strong linear connection between the soprano's "D" and its initial "C#" go a long way toward justifying the apparent infraction.

Adapt the harmonization of Example 6 to the melody shown. Begin with a close position triad to help keep alto and tenor from getting too low.

The inner voices almost write themselves: the C natural in the alto on beat four of bar one creates no difficulties because it is not adjacent to any form of scale degree seven. The tenor moves naturally stepwise in its meandering descent from scale degree 5 to scale degree 3.

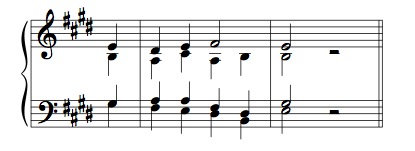

Let's try one last 'summary' example, which will use all of the six-four types explained in this Hub: the arpeggio/alternating type; the neighbor type; the passing type; and finally the cadential.

The order in which the six-four chords were given above was the order in which they were presented in this Hub--but it is also a workable order in which to use them to harmonize this melody. In addition to the appropriate six-four figures, use a first inversion leading tone triad in measure 1, a root position IV chord in measure 2 and a first inversion supertonic in measure 3. Begin, as always, with the bass line.

In the first bar, the bass arpeggiation is arranged to avoid doubling the third on beat two, and to stay in the middle of the bass vocal range. (In a higher key, it would have been tempting to keep the arpeggiation a straight descent, but if we hadn't reversed direction in the arpeggiation, the low Eb would have been difficult to avoid.) From there, the contour of the bass rises to the dominant scale degree at the final cadence, setting up our newly familiar octave drop figure.

Now add the inner voices, beginning with an open chord voicing.

Doc Snow on Wordpress.com!

- snowonmusic | A music theory blog that's NOT all work!

An alternate (and more casual) place to ask any musical questions that may linger in your mind... plus, musical parlor games!

Note the voice exchange between soprano and tenor in the first two beats.

The alto is straightforward throughout, but in the tenor there are several alternate possibilities from beat 3 of bar 2. All are correct; the one selected offers the most vocal drama as it takes the tenor line into a high (and therefore bright) vocal register. Note how the leap is prepared by stepwise motion contrary to the leap, and how the leap is followed by contrary motion as well (albeit not stepwise.)

Other possibilities are not shown. (How many can you find?) The differences between them are minimal in a piano rendition, but would be clearer (if still quite subtle) in an actual vocal performance.

With the 'grand finale' complete, it's time to close this Hub. In doing so, we also close out this series on inverted triads, and mark a big milestone in the history of these part-writing Hubs: we've now covered all diatonic triads, in all inversions. That's big.

Of course, there's more. We haven't dealt with chromatic harmonies, or with tonicizations or key changes (partially overlapping categories.) Nor have we dealt with seventh chords. But watch for Hubs on the latter. They are on the way!

Other (Music) Hubs by Doc Snow

- Strange Days Again: Remembrance And The Doors' Sophomore Album

Music and memory intertwine: The Doors' most innovative album, "Strange Days," analyzed and remembered. What it was, is, and why it mattered so much to me. - Part-writing Inverted Chords: Mediant, Submediant & Leading Tone Triads

Part-writing is an essential discipline in really mastering traditional music theory, and triads in inversion add great nuance and musical flexibility to the harmonic palette. This Hub examines triads built on 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees. - How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently, Part Two

Practice more efficiently and get better faster with these practical strategies! Topics include practicing for continuity versus practicing for problem-solving; changing the terms of the practice problem; and practicing with a metronome. - Understand Chords: Chords In Keys (Part Two of a Series)

Chords are important musical building blocks, of course, but they aren't just isolated 'things.' Rather they belong more or less naturally in certain 'keys.' Learn about them here!