Part-writing Inverted Chords: Interlude--Passing & Auxiliary Tones

This Hub is part of a larger grouping of articles describing the ins and outs of correct part-writing in common-practice music. (That is, most music written from roughly 1700-1900, and much music after that, too.)

The Hub is meant to be fourth in the second series, which deals with part-writing inverted triads. But as an interlude, it can be read (and worked) independently.

I wrote 'worked' since this series of Hubs not only explains and illustrates the concepts presented, but also offers practice exercises to help you build your part-writing skills. To get the most out of those exercises, do them on paper before clicking through the 'answers' provided. For convenience, I've given a link to a site from which you can download manuscript paper to print out.

- Free printable staff paper @ Blank Sheet Music .net

Free printable staff paper

In the part-writing Hubs so far, relatively little has been said about rhythm, or about melody; and the melodies of our musical examples have been almost exclusively composed of chord tones. But in the musical 'real world,' rhythm is very important and melodies usually make considerable use of tones which don't belong to the chord.

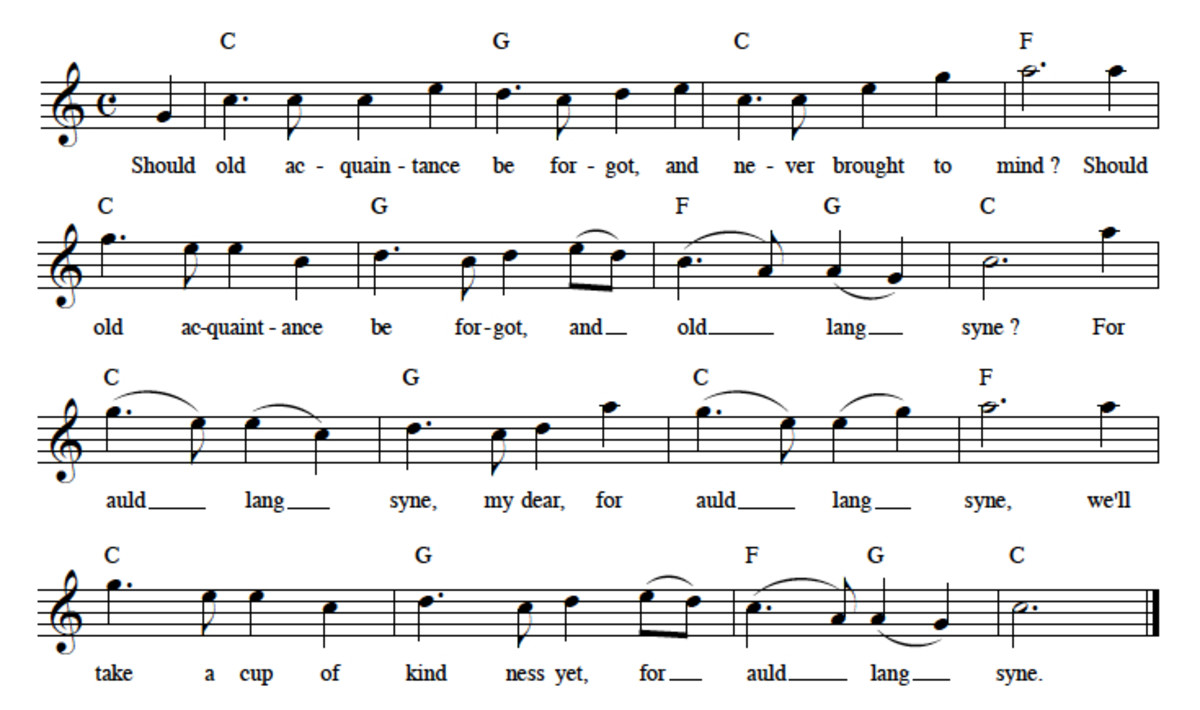

To illustrate this, notation and video for the melody we've used several times as an illustration, "Auld Lang Syne," is given below.

The circled tones in the melody do not belong to the chords sounding--logically enough, we call these "non-chord tones," or "non-harmonic tones." Their use gives melodic flexibility, nuance and musical expressiveness--you might say that they bring the melody to life.

VEx 1

Are You Ready For This Hub? Here's What Came Before.

- Part-writing Inverted Chords: Mediant, Submediant & Leading Tone Triads

Triads in inversion add great nuance and musical flexibility to the harmonic palette. This Hub examines usage of inverted triads built on 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees. - Part-writing Inverted Chords: The Supertonic In First Inversion

"Supertonic in first inversion" sounds forbidding, but this chord is a favorite choice to prepare a dominant chord in everything from Bach to Ellington. Learn how to use it here. - Part-writing Inverted Chords: Primary Triads In First Inversion

Learn to write tonic, dominant and subdominant in first inversion--these explanations, illustrations, and practice examples make it easy! - Part-writing Chords: Summary I

A 'syllabus' and summary for Doc Snow's innovative Hubs on the essential musical skill of part-writing. Sequence, content and links--plus a summary of part-writing 'rules.'

In this Hub we'll explain the two most common forms of non-harmonic tones--"passing tones" and "auxiliary tones"--and practice using them in four-part settings. We'll assume knowledge of the basic rules of common-practice part-writing and of Roman numeral chord names. If this sounds unfamiliar, you may wish to go back and work through one or more of the preceding Hubs, which are linked in the right-hand sidebar.

(They are given with the most recent Hub first. If you wish to review the part-writing 'rules', the summary Hub for Part-writing Series One is your ticket. It briefly describes these rules, and provides links to the individual Hubs in which they are introduced.)

Passing Tones

There are several types of non-chord tones, each with different characteristics and 'personality.' Some composers or styles may favor a particular type, which then becomes part of the character of that body of work.

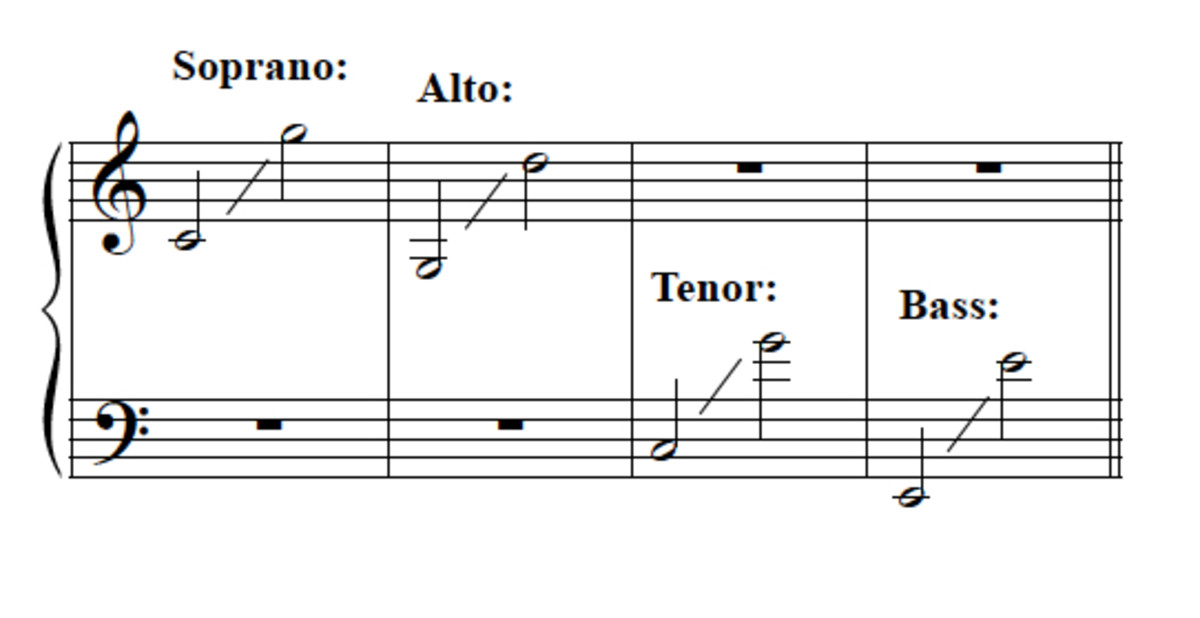

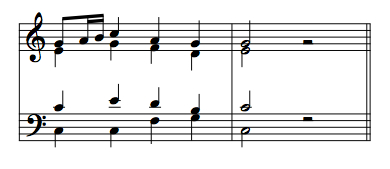

But probably the most common form of non-chord tone is the passing tone. To begin our consideration of the passing tone, let's suppose that we are working with the brief chord progression shown below.

I think we can all agree that it's a very plain-sounding six seconds or so. However, we can add interest by linking the chord tones in the soprano with non-chord tones:

The rhythm is now livelier, and the melody feels as though it is more directed and energetic.

Not surprisingly, these non-chord tones are all passing tones--they serve to create linear scale segments whose end-points are chord tones. (That is, the non-chord tones 'pass' the melody between chord tones.) A common way of stating this in music theoretical writing is that "passing tones are approached by step and resolved by step in the same direction."

Notice, too, that the chord tones are on the beat, while the passing tones are not--they fall on the unaccented eight-notes 'between' beats. This is the most typical pattern, though not the only one.

One last point: the chord tones do not always need to belong to the same chord. For example, the G on beat four of the first bar is connected to the E of the following bar. The G belongs to the dominant triad, G, while the E belongs to the tonic, C. This does not affect the status of the passing tone in any way--it still connects two chord tones.

Let's practice using passing tones. Here is a brief passage in four parts, using the same chord progression as the examples above. We'll add passing tones to the soprano. What are the key and scale degrees of this melody?

Here we are in the key of Eb, and the scale degrees of the soprano tones are 5-3-7-2-1. Can you find the correct places to add passing tones according to the model above?

As shown, passing tones fit in naturally where there are skips of a third in the melody.

So far we've used passing tones with repeated chords. However, as mentioned above, passing tones often occur between melody notes harmonized with different chords. The tones will still be separated by third, typically, but the fact that the bass moves as well poses some complications.

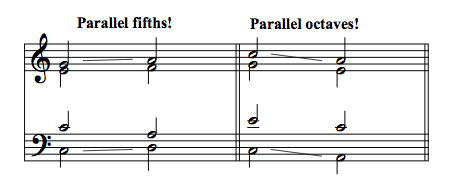

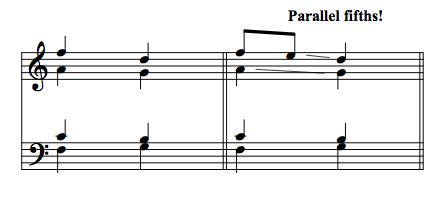

We've seen in previous Hubs that in common practice music, parallel perfect fifths, octaves and unisons are normally forbidden. This is illustrated below:

Since bass and soprano move in the same direction, by the same interval, their motion is parallel. And since they are separated by the intervals of a perfect fifth (plus a octave, which we can disregard for this purpose) in Example 3a and a perfect octave in 3b, they are then examples of the forbidden parallel perfect fifth and parallel perfect octave (often just called 'parallel fifth' or 'parallel octave' for short.)

(Note that parallel perfect intervals between any pair of voices is unacceptable. In a four-part texture, there are 6 possible pairs of voices to check for objectionable parallels! That's why it is more efficient to concentrate on using 'normal' voice-leading patterns, rather than on avoiding infractions of rules--the approach taken in this series of Hubs. Still, it's important to understand the faults that those normal patterns avoid.)

Adding passing tones can create such forbidden parallels. Observe what happens when passing tones are added to fill in skips of a third, if another voice moves stepwise in the same direction:

Definitely a fault to be avoided! Although the first version is the normal, totally approved voice-leading of a IV-V progression, the addition of the passing tone creates parallel fifths between soprano and alto.

Here's a practice question which has the potential to create forbidden parallels by the addition of passing tones--as well as the potential for perfectly legal passing tones! The challenge is to add all possible 'legal' passing tones, while avoiding the forbidden ones.

Note that passing tones are a bit of a 'lose-lose' proposition in part-writing terms, in that they can create forbidden parallels, but they can't disguise or break up forbidden parallels already defined by the chord tones. As we've just seen, it is quite possible to create forbidden parallels by poorly-chosen passing tones.

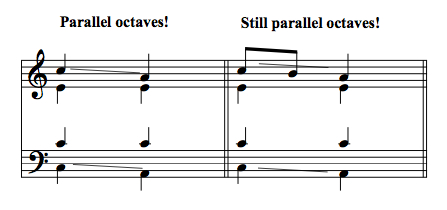

But you can't do the reverse--that is, you can't 'break up' parallels by inserting passing tones. The ear still picks up them up.

For example, the first measure below shows a progression with parallel octaves between soprano and bass. You might think, optimistically, that the passing tone added to the soprano in the second measure's version 'breaks up' the parallels. But they are not sufficient to disguise the faulty underlying structure.

This won't be much of an issue in this Hub, since I won't be throwing faulty progressions at you, but the point is worth keeping in mind for when you write your own progressions.

Passing tones are probably most common in the soprano voice, which tends to form the melodic focus, but can occur in any voice. (They certainly do in the chorales of Bach, which are an important source of 'norms' for all four-part harmony exercises--such as these!)

Now let's try adding passing tones to the bass.

The only spot for the bass passing tone is between the first two chords. Note the existing passing tone in the soprano, and the fact that the bass passing tone forms a consonant interval--a perfect octave--with the soprano's passing tone. This is desirable when using simultaneous non-chord tones: they already clash with the underlying chord; better that they don't also clash with each other.

Finally, let's add passing tones in all voices--there is an opportunity in all four. But beware of creating parallels.

Obviously, many passing tones! But the soprano in beats one and two does not afford a legitimate opportunity--adding the passing tone 'C' at that point would create parallel fifths with the alto.

Note how the passing tones on the second eighth of bar two, beat one create a complete triad A diminished triad, dissonating with tenor's Bb--the only remaining chord tone.

Another typical use of simultaneous passing tones is heard on the second eighth of beat one, bar three, where the bass and soprano move in parallel thirds. This is very effective, and can involve any pair of voices.

Finally, notice the particular scale degree pattern heard in the alto at the final cadence. The 5-4-3 descent is very frequently heard indeed (especially in alto and tenor voices). Its developments will be considered at some length in a later Hub.

I hinted above that passing tones are not limited to the most typical pattern which we have been examining so far. There are two passing tone variations we must mention.

First, passing tones sometimes do occur on beats--even on metrically strong ones. When this occurs, they are usually labeled "accented passing tones."

The voice-leading pattern does not change otherwise--that is, the passing tone is still approached by step, and resolved by step in the same direction. But because the non-chord tone occurs in a more prominent rhythmic position, the dissonance is more pronounced, creating a 'spicier' sound:

Try redoing first two passing tones of Example 1 as accented passing tones. Leave the last one as it is. Can you see why it doesn't work well as an accented PT?

(Example 1 is given again below so you don't have to scroll back up the page.)

As you can see, the tones are the same as in Example 1; only the rhythmic positions change. This is not, perhaps, the most characteristic usage of accented passing tones--the line seems much more natural when the passing tones are not accented--but it is a convenient way to introduce them. We'll see accented passing tones in a more typical context in a moment.

But for now, let's go on to consider our second point about passing tones. So far all our passing tones have 'filled in' a third; but sometimes it is permissible to span a leap of a fourth with two consecutive passing tones, as shown below.

In this example, the consecutive passing tones fill in the space between fifth and root of a single chord. Since the passing tones are only sixteenth notes, neither is accented. But one sometimes sees (and hears) consecutive passing tones in eighth notes, as shown:

In this version, the second passing tone is accented. Notice again the more emphatic harmonic clash of the dissonance on the beat.

Finally, two consecutive passing tones can sometimes span a chord change, as shown in Example 8. It is perhaps a little less usual, but is far from rare.

Try adding consecutive passing tones in a pattern similar to the last example. (Soprano only.)

The submediant (vi) triad on beat two uses the incomplete voicing (triple root, no fifth) in order to avoid a excessive leaps in the tenor voice, even though such a voicing is quite unusual for this chord.

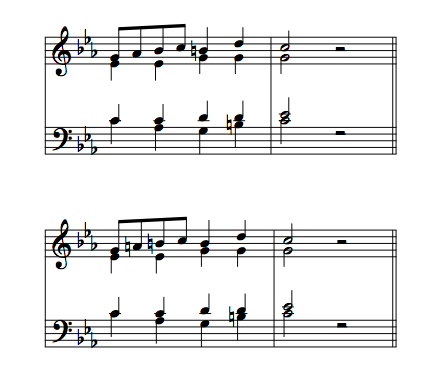

One last point about passing tones in minor: the prohibition against mixing the lowered sixth and the raised seventh, thereby creating the forbidden melodic interval of an augmented second, definitely applies to passing tones. But it does not always apply in the most straightforward manner. Consider, for example, the following:

Which forms of the sixth and seventh scale degrees should we use here? Is the first version correct, or do we need to raise the A and B as seen in the second version? One might reason that the second version follows the melodic minor scale more closely; it is an ascending scale segment, so the ascending form of the melodic minor scale would seem appropriate.

On the other hand, the A natural would form a 'false' or 'cross' relation with the A flat in the bass of the succeeding chord; and one could not correct the bass to match since that would create a root position diminished triad.

Let your ear be the judge:

Most listeners will prefer the first version; there's a real 'sourness' to the false relation.

So how does one choose when to raise sixth and seventh scale degrees?

There are many shades of grey possible in this area, and hard and fast rules are not practical. The best advice is to think as clearly as possible about the alternatives one faces, and, if at all possible, play throught the passage you are trying to harmonize. Your ear is an experienced musical judge, or you would scarcely be reading this. If you can bring that wisdom to bear, it will serve you well.

Auxiliary ('Neighbor') Tones

By contrast with passing tones, auxiliary or neighbor tones serve to embellish a single tone--they do not connect different tones. The most typical auxiliary note pattern is shown below.

Here the auxiliary tones occur on the unaccented off-beats, and are below the chord tones which they decorate. A common description of this pattern says that "auxiliary tones are approached by step and resolved by step in the opposite direction."

In addition, maintaining a similar contour to Example 1 necessitated the use of the simultaneous "chordal skips" on beat two. In such contexts, voice leading can be a bit freer than usual; in particular, similar fifths and octaves tend to blend into the overal sound of the chord.

Try adding auxiliary tones to the soprano voice, using the example as a model.

There are really only two possible places for auxiliaries, as shown, since adding an quxiliary tone to the "Eb" on beat one of bar two would create parallel octaves. Note how the auxliliary notes interact with the passing tones in the bass: the non-chord tones are consonant with one another, as we discussed above, and where the two patterns generate parallel motion, it is at the intervals of a sixth and a third.

It's also possible to apply auxiliaries above the main note, rather than below it. In this case, they are called, logically, "upper auxiliaries." The effect of upper auxiliaries is a little more pronounced than that of lower auxiliaries. It's by no means uncommon to encounter them; in fact, it's common enough that it is a good practice always to specify either 'upper' or 'lower' auxiliaries.

Can you convert the lower auxiliaries of the previous example into upper ones? Here is Question 7 once again, for convenience in contemplating that question.

As shown, upper auxiliaries don't work in the same locations; the first one (beat one) creates parallel octaves, the second (beat three), "quasi-parallel" fifths. (Though they are perfect-diminished, which may be acceptable at the beat level in 4-part harmony, they really don't work in two part at sub-beat level; they are much too prominent.)

However, it is possible to use an upper auxiliary on beat one, bar two. The result is a more interesting melodic shape, and parallel thirds between soprano and bass.

Try a new question in the application of upper auxiliaries.

Fairly straightforward, I hope! But this is an interesting example in its handling of sixth and seventh scale degrees. Can you explain why the choices shown were the necessary ones?

Accented auxiliaries can be formed in the same manner as accented passing tones, and with analogous effect. Try converting the auxiliaries of Question 8 into accented ones.

Do you like or dislike the result? Some might feel that the increased emphasis on the dissonances give a Romantic quality to the harmonic language.

Let's try one last question. In this one, let's combine auxiliary and passing tones, adding them to both soprano and bass voices. (But give priority to the soprano--that is, if adding to both creates a problem, add to soprano only.)

Doc Snow on Wordpress.com!

- snowonmusic | A music theory blog that's NOT all work!

A music theory blog that's NOT all work! It's a casual hang-out for those who like to talk (and think) about all things music!

And that's our interlude. It should leave you with a solid understanding of the two most common forms of non-chord tones. (There are others, but we can leave them for another time.)

It also leaves us with the ability to create more musical and (frankly) more interesting musical examples. We'll use that ability in the following Hubs, which continue to explain the usage of inverted triads--and particularly, chords in second inversion.

Other Music Hubs by Doc Snow

- Understand Chords: Beyond Seventh Chords To Chord Extensions--Ninths, Elevenths And Thirteenths (Par

Extended chords-ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths-are undoubtedly hipper than the average triad. But what are they, how do you use them, and, most of all, what do they actually *sound* like? - Strange Days Again: Remembrance And The Doors' Sophomore Album

Music and memory intertwine: The Doors' most innovative album, "Strange Days," analyzed and remembered. What it was, is, and why it mattered so much to me. - Better Faster: Top Ten Music Practice Tips

"Practice, practice, practice!"--But what about practicing *smarter*? This article gives ten useful tips to do just that. Get better, faster! - How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently, Part Two

Practice more efficiently and get better faster with these practical strategies! Topics include practicing for continuity versus practicing for problem-solving; changing the terms of the practice problem; and practicing with a metronome.