How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently, Part Two

How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently (Part Two)

So many ways not to practice music efficiently! In Part One we looked at a few of these ways, and found that they often come in complementary pairs. For example, you sometimes hear the advice that you should:

“Always try your hardest!”

Sounds reasonable, at least until you try it—or until you read the complementary opposite advice:

“Don’t ‘try’—just let it flow.”

Which is it?

Well, neither! “Flow” is certainly important, but so is effort. It’s not easy to do many of the things we need to do as performers; and it’s not easy to teach ourselves the mental and physical skills we need. Effort is just unavoidable.

Yet effort taken to an extreme becomes counterproductive--you inevitably begin to involve muscles that are unhelpful. You must balance “effort” with the precision that comes as things “flow.” You must find a middle way combining elements of both extremes.

A pretty simple example of a complementary pairs of suggestions concerns the use of the metronome in practicing. You might hear either of these:

1) Always practice with a metronome

2) Never practice with a metronome

#1 is probably more common than #2, but both have been said. The first is common advice in the world of pop music, though it’s occasionally encountered in classical realms as well. It makes sense in popular styles particularly, since the ability to hold a consistent “groove” is very important--especially for drummers and bassists. At a more sophisticated level, it’s also important to be able to deviate from strict time without losing precise track of the beat. And metronome practice definitely has its place in developing these skills.

Metronomes as public art

Click thumbnail to view full-size

So why would anyone advocate “never” using a metronome? Well, there is a danger of coming to rely too heavily upon obvious clues to the meter. And it is important to be able to generate one’s own “internal” beat—something that can only be tested by turning the metronome off!

Moreover, in Classical styles—especially in 19th century practice—intentional variations in tempo are a very important expressive feature of the music. Using a metronome just gets in the way of trying to practice these; some writers even feel that a musician practicing too much with a metronome may come to sound a bit “mechanical” him- or herself.

Clearly, the “middle way” is right; a metronome is a most useful tool, but is not equally useful at all times, or in all situations. Sometime you just need to turn it off.

A related concept would be using various technologies to check your tuning. I wish I had spent much more time checking mine when I was a developing player. It is easy, alone in the practice room, to overlook intonational faults, but if you always do, you may be allowing your playing to be less beautiful than it could be.

Today we have (in addition to the venerable piano—an under-utilized resource for most of us) chromatic tuners and sampling practice software to help us with this aspect of our playing. If we don’t use them, we have nobody else to blame.

Another “all or nothing” pair—one you may not have heard—is this:

1) Always listen for your mistakes

2) Don’t listen to your mistakes

The reason you may not have heard these is that they are pretty clearly not good ideas, once you actually say them out loud. What you do hear, though, is advice which in practice seems to suggest one or the other of these not-so-good alternatives.

Of course, it’s pretty obvious that that’s only a beginning—nobody would pay to hear (for instance) a performer who consistently plays flat, behind the beat, and with all the tonal beauty of fingernails on chalkboard! But for all I knew, that’s just what I might have been doing; I wasn’t checking my intonation, or timing, or tone quality to actually be sure. In short, I wasn’t really listening to myself.

So should you “always” be listening for your own mistakes? It depends what you mean by that. At some level, we must always be monitoring our pitch, our timing, our sound. But when you are performing, the last thing you want to focus on is your mistakes.

I recall a violin master class I sat in on long ago: a young hotshot was ripping through a concerto movement. We were all wowed: she had such tone, such technical assurance, such accuracy! But then, maybe three-quarters of the way through, came a small slip—I no longer remember exactly what: an actual wrong note? a momentary hesitation that put a “hitch” in the rhythm? an instant’s flaw in the intonation?

No matter—the violinist heard it. And she couldn’t forget it. Soon, another slip, a bit worse than the first. And another, and another. She barely finished the movement, concentration in tatters.

Much better--in a performance situation!--to forget all about your mistakes. There will be a few—but if you’re lucky, they may be small enough that only you will notice. So forget about them; you need to be on to the next bar, not dwelling on the measure you just “damaged.” You can’t do anything about it now, right?

So listening for mistakes can be bad, too.

But not all advice falls into this pattern of complementary opposites that I've been following so far. Here's a pair of practice methods that doesn't—I won’t call them “suggestions,” since nobody actually advocates them! Yet many musicians, especially young ones, practice as though they were the best and most iron-clad of rules.

1) Always start at the beginning of a piece

2) Never practice slowly

Though these “non-rules” don’t form a complementary pair of opposites, they are complementary in the sense that together they describe an approach to practice you could call “literal.” In this approach, every practice session is treated almost like a performance—except that any mistake is cause to stop and start over again.

I suspect that there’s an emotional reason for the prevalence of this kind of practice. Many players, and particularly young ones, are prone to worry that “this time,” they might not succeed in mastering the material. So there is a rush to prove that “they’ve got it"--then the worry can be minimized or eliminated.

But it pays dividends to learn to tolerate a little worry for a while.

Practice sessions are supposed to make you play better, which is to say that they are about solving problems. To do that best, it often makes sense to change the material you are practicing temporarily in order to help you play it better.

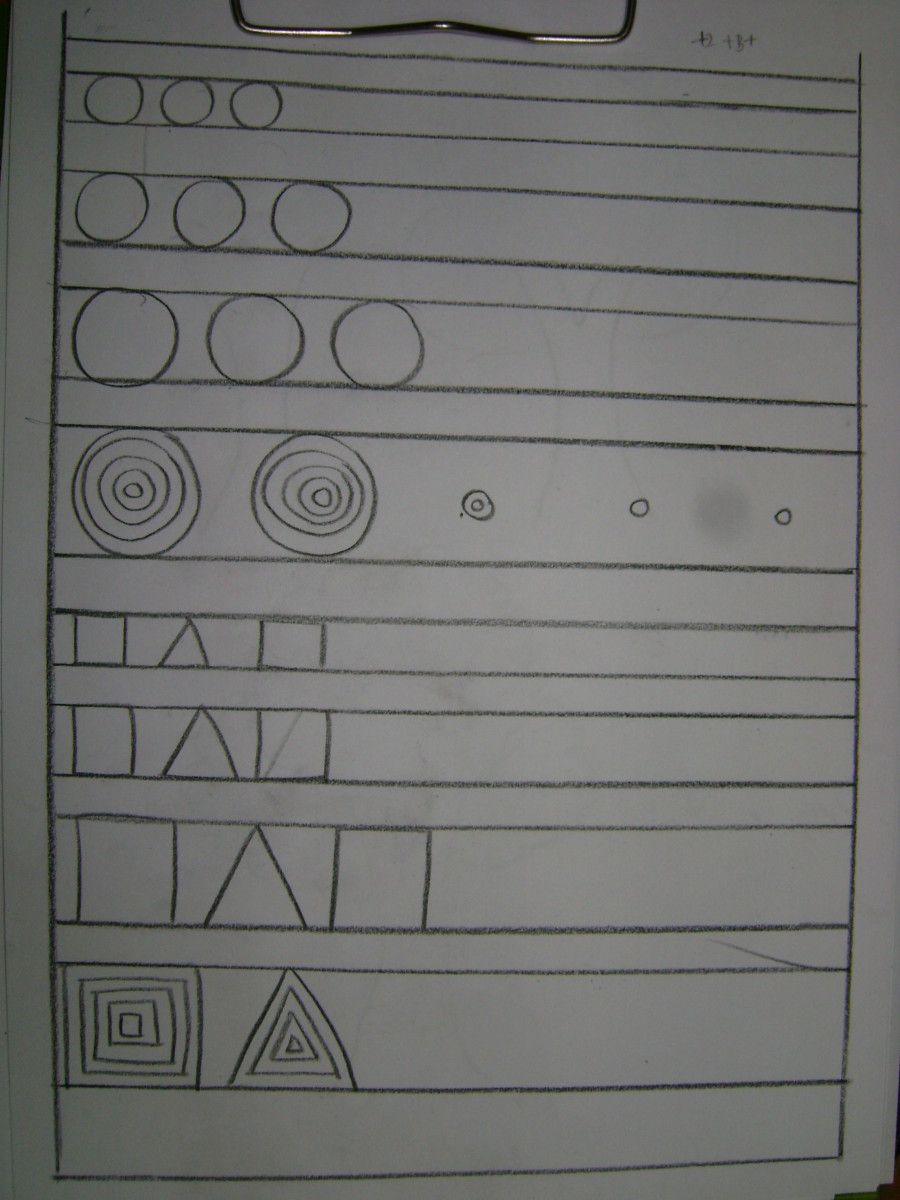

Some suggested alterations you can make:

1) Play it slowly! The most basic change is to tempo. This affords your mind and body time to “do it right.” Many generations of experience attest that slow practice is a great tool to nail down tough licks.

Be patient, though; a minimum of three satisfactory repetitions is desirable before you increase the tempo, and many more than that may be needed in some case.

By the way, slow practice is great either with, or without, a metronome; but it’s very important to keep a consistent tempo in your slow practice. If you struggle to do that, then a metronome is a great help.

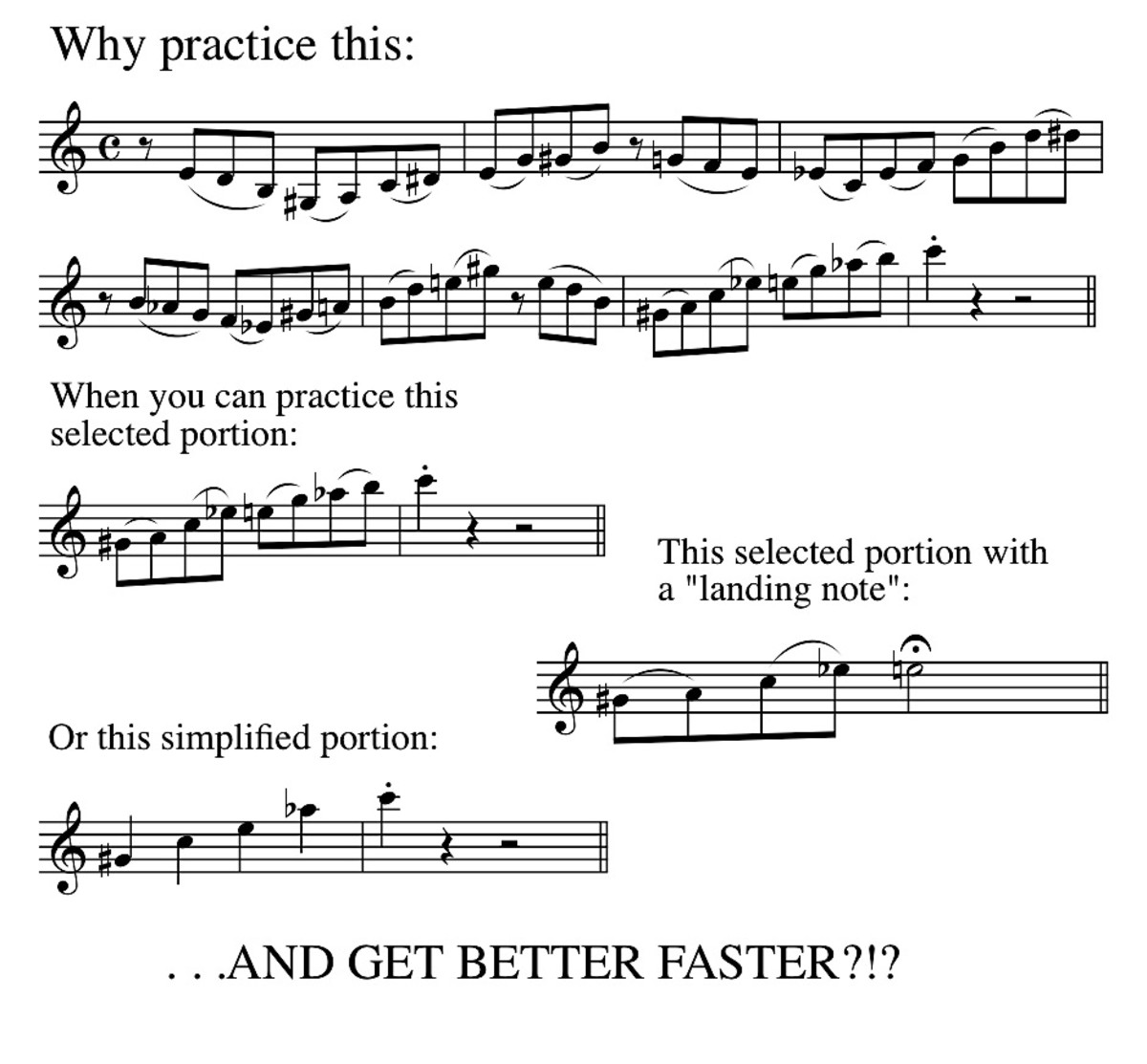

2) Play just a selected portion! For efficiency, practice only what you need to practice—if measures 1 through 16 are already fine, why play them over and over? Start at measure 17, by all means! And if measures 18-27 are fine, I wouldn’t play them, either. I’d just go on to 28.

A variation is to pick tricky notes as “landing spots”—put a mental pause sign on them and play the passage leading up to them, “landing” on them and holding them. This really helps get then into your mind and body. It works great it ensemble rehearsals, too, helping sharpen both pitch and rhythm! (See the musical example below for a written-out instance of this tactic.)

It is also okay to simplify passages--for example, I've been known to clean up rhythm and absorb the melodic "core" of a passage by practicing just, say, the notes on beats, or just on the eighth notes. It can be surprisingly helpful.

A final trick that comes under this heading is to practice pieces--especially those for which physical endurance is important--“backwards.” That is, play the ending passage first, then work your way, section by section, back to the beginning.

The idea is to teach your mind and body to play the ending while physically fresh and strong. The usual "start at the beginning every time" method makes it very easy to teach yourself instead that an essential aspect of the ending “is” you feeling tired, tense, and uncertain. Not a good idea, that!

3) Change the instrument! Singers sometimes play over their parts on piano as one way of helping to learn them. The converse happens when players sing their parts. This is a good trick to use when the problem isn’t so much getting a lick into one’s fingers, as into one’s brain. It can be just so helpful to sing it instead of just playing it one more time!

Similarly, sometimes it’s more helpful to clap or say a rhythm than to play it.

Three Singing Trumpeters

Click thumbnail to view full-size

Trumpet Players Weigh In On How Singing Helps

- Singing - View topic: Trumpet Herald forum

A thread in a trumpet forum draws overwhelming responses advocating the value of singing as a practice technique (and double!)

4) Change the key! The trumpeter Adolph “Bud” Herseth is said to have been fond of practicing passages in transposition, and it’s a method that I’ve adopted at times. It does keep things fresh, and allows you to play a passage with more sense of “flow” in an easier range, then transfer it gradually into the correct key. And of course, you are practicing the handy skill of transposition as an added bonus.

Finally, let me suggest that these “hows” and “how nots” suggest a useful way to think about your practice time. For best results, you should be clear in your own mind that your are either:

1) Practicing for continuity, or

2) Practicing to solve problems.

In practicing for continuity, you are primarily trying make sure that the physical and musical problems a piece poses are not, in fact, greater than the sum of their parts! You are trying to “get through” the piece. In this mode, you are following Bud Herseth’s advice to “perform, not practice.” In fact, you’re “practicing” letting go of any errors that you may happen to make.

In part, you are also reassuring yourself that you do “have it.” (Yes, I said earlier that it's helpful to learn to tolerate some worry--but we're all human after all, and we all need to build a confidence that's well-founded.) And in part you are making sure that everything is working in its real context--physically, musically and artistically.

In practicing to solve problems, you stop when you "take a mismake." Right away. And you deploy all the tricks you know to address problems as quickly, efficiently and dispassionately as you can. You listen for mistakes. You change whatever you find helpful to change. You are patient and forgiving of yourself—you remember that mistakes in the practice room are not moral failings. You use your metronome, you sing over parts, you check your intonation and sound.

And by golly, you improve.

- How (Not) To Practice Music Efficiently, Part One

"My How (Not) To Hubs are, I hope, fun, but my qualifications to write them do vary a bit from topic to topic. As far as the present Hub goes, though, I'm truly an expert..." - How (not) to replace a door

Replacing an exterior door isn't all that hard. But it's easier if you don't let it deteriorate for quite as long as I did. . . - Global Warming Science And The Wars: Guy Callendar

The story of the man who brought CO2 theory into the 20th century. "Nearly everybody likes to be right, and scientists perhaps more so than the rest of us. Their professional lives, after all, are dedicated to uncovering the truth..." - Armsful Of Clocks: A Meditation

A workday epiphany. "It was still dark when I arrived. Six AM, time for the ragged end of the night shift clocking out under the fluorescent glare, and the headlights of early commuters slicing a dark..." - Through A Glass Darkly: Equinox Reflections, 2010

How I watched the sea ice melt--how it felt, and what it means. "It's just past the fall equinox, that day when the year turns from light to dark, summer to winter. Days have been growing shorter since the summer solstice..." - Global Warming Science: A Thumbnail History

The real story of global warming science history. "On August 14, 2010, retired astronaut Walter Cunningham wrote: About 20 years ago, a small group of scientists became concerned that temperatures around the Earth..."