Amy Seidl's "Finding Higher Ground": A Summary Review

"Finding Higher Ground: Adaptation In The Age Of Warming", by Amy Seidl. Beacon Press, 2011. Reviewed August, 2011.

Amy Seidl’s Finding Higher Ground is a rarity: a book about climate change that is at once realistic and hopeful. Its realism is captured in the recurrent sobriquet “the Age of Warming,” which she applies consistently to our time. It also reflects her acceptance of the losses which the Age of Warming will entail:

It is true: we face a turbulent future. There is no doubt that there will be tremendous species loss, human suffering, and conflict that arises from compromised landscapes. . . the world will change beyond what most of us can comprehend.

Its message of hope is that adaptation has already begun:

While mitigation climate change is essential adapting to and through centuries of warming is paramount. . . the stories of animals, plants and people adapting to a warming world express trust in our ability to adjust to changing conditions, even radical ones, and to establish a voice for resilience in uncertain times.

This duality of attitude--facing loss squarely while preparing to endure--is mirrored by a duality of perspective: Dr. Seidl’s eye as a scientist brings us the objective world of biology and ecology, while her sensibilities as concerned citizen and mother bring us her personal world. (She is the mother of a family which working to adapt to the ‘compromised’ world that she so clearly envisions.) Throughout the book, these two viewpoints alternate--though the balance tends to shift toward the latter as the book progresses. The chapter headings perhaps suggest this:

•Adapting to a Carbonated World

•Fitting In

•On Migration

•Feast or Famine

•Our Oldest and Newest Energy

•Localizing Home

•Self-Reliance

•The Pragmatisn of Adaptation

•Epilog: Persistence

“Adapting to a Carbonated World” begins by briefly describing some of the potential risks facing us, and discussing the dilemma of “mitigation”—that is, of reducing carbon emissions in time to avoid permanently excessive atmospheric concentrations—versus “adaptation”—the means by which humans can ameliorate some of the harms coming our way.

Though industrialized countries can adapt and mitigate “hand in glove,” she writes, less-developed ones are less able to undertake either adaptation or mitigation. Indeed, in some cases they already contribute “essentially nothing” to the problem.

For them, adaptation, and in some instances survival, dominates their response to a changing planet, and their sovereignty depends on mitigation by other nations. The conservation biologist David Orr likens proponents of mitigation to individuals who choose to ‘turn the water off in an overflowing tub before mopping.’ While that seems to make sense, proponents of adaptation from the least developed nation realize they have little access to the spigot and may have to evacuate the flooded house altogether.

She continues by emphasizing the too-little appreciated fact that--in the words of climate scientist Susan Solomon--“atmospheric temperatures. . . are not expected to decrease significantly even if the carbon emissions cease” and that warming is essentially irreversible over a “time scale exceeding the end of the millennium in year 3000.” We have the choice to change our “reckless and self-destructive behavior,” still--yet the Copenhagen conference in 2009 was anticipated to enact carbon targets that would have led to 770 parts per million of atmospheric carbon. That represents a doubling of current levels—a figure, according to James Hansen, “beyond which life on Earth is not adapted.”

In the event, of course, no agreement was reached.

For climate activists, this was “rock bottom.” But as Dr. Seidl remarks, humans have repeatedly had to face rock bottom. For instance, the Norse colony in Greenland hit the ultimate rock bottom in the fifteenth century: complete extinction.

It’s a sly narrative strategy to consider Norse Greenland, since that era has been widely hyped by those unwilling to face the reality of the Age of Warming as a unique human-caused event. But Dr. Seidl asks a substantive question: how was it that the Norse died out in a place that had been their home for five centuries, where they had grown from a handful of initial colonists to perhaps seven thousand, even as the Paleo-Eskimos thrived alongside them? This would seem to represent a stunning failure of cultural adaptation.

From there, Dr. Seidl turns to viticulturist Deirdre Heekin, just one of a number of people we are to meet in Finding Higher Ground, who is actively adapting now, by discovering grape varietals likely to thrive in the Vermont of the future. (Projections indicate the Vermont climate at 450 ppm would eventually resemble that of Atlanta, GA, with an average January temperature of 40 F.)

In “Fitting In” Dr. Seidl’s biologist’s eye and poet’s ear—she studied poetry as an undergraduate, in addition to natural science—combine to give us really lovely writing--limpidly clear, yet evocative. For example, Dr. Seidl regularly grows mizuna-- a “spicy salad green that germinates well in cool conditions” and also “our best illustration yet of how plants could adapt to climate change.” In introducing it, she writes:

Reddish grains, the size of poppy seeds, go easily into the soil. . . In one week’s time, lime-green sprouts contrast with the dark earth around them. . . In a month I clip the fern-like leaves of mizuna with a pair of children’s scissors we keep for harvesting delicate lettuce and herbs.

Arthur Weis, of the University of California at Irvine, was studying the mizuna genome in 1997, using wild populations that had ‘escaped’ from cultivation. He refrigerated unneeded seed, sending it into dormancy. This thrifty impulse was rewarded in 2004, when he realized that his ‘sleeper’ seed could be compared to wild populations which had been surviving extreme drought conditions in the meantime—for seven generations, in fact, since mizuna is an annual plant.

A “common-garden” experiment showed the descendent seed to have become significantly drought-adapted: under watering regimes simulating drought conditions, 90% of ‘descendent’ plants survived, while survival for the ‘sleeper’ plants was only 62%. Clearly the drought had induced genetic adaptation in a very short span of years.

Dr. Seidl contrasts this genetic response with “phenotypic plasticity,” in which individuals and populations can change behaviorally or physiologically without genetic adaptation. As example, she cites the behavior of the red squirrel as studied by University of Alberta biologist Stan Boutin.

In the boreal forest of the Yukon, he found that due to phenotypic plasticity, female red squirrels were giving birth as much as three and a half days earlier. Warmer temperatures made for more abundant spruce cones—a staple for the squirrels. Better nutrition made for more rapid fetal growth and shorter gestation. (This is an example of a species benefiting from warming. For slight warming, such examples abound, but they become much rarer for warming beyond 2 degrees C--greater warming becomes more and more damaging on balance.)

But there was genetic adaptation, at work, too: pups born earlier were at an advantage, and survived better on average. This provided an evolutionary reward to the squirrel mothers most responsive to the improved nutrition. The two effects combined to advance birthing dates over the study period by two full weeks.

As the chapter’s final non-human example, Dr. Seidl considers the mutualistic adaptation of pitcher plants and pitcher plant mosquitoes. Biologists Christina Holzapfel and William Bradshaw found that, like the mizuna and the red squirrel, the pitcher plant mosquito has adapted genetically, remaining active deeper into the summer in order to take advantage of the longer warm season. As with most such adaptations, this strategy is not without its risks: an early freeze could prove devastating. But so far--to the regret, perhaps, of New England campers--the pitcher plant mosquito is doing just fine.

But what of human adapation? For us, Dr. Seidl writes:

. . . natural selection works culturally and biologically to affect behavior. The science of human genetics has shown that culture can be a powerful force for, and buffer against, selection. . . culture itself can be a selective agent.

Most pertinently for the Age of Warming, choice of technology: like the designs of Polynesian canoes, the least appropriate technological choices for a given situation will bring with them the highest probability of fatal outcomes. Those who choose well survive and reproduce, and their technology will be copied. Here biological adaptation and cultural adaption become intertwined.

“Climate change is nothing less than the opportunity to fit in with our environment” says Dr. Seidl--but the "fitting in" process is hard on the misfits.

It would be unnecessary and unhelpful to trace the entire book in the kind of detail given so far—though the telling details and fascinating personalities make it tempting.

Briefly, then, “On Migration” gives us the changing migrational strategies of Pacific black brant geese; the Eurafrican songbird known as the “great tit;” the brown pelican; the white marbled butterfly—and of humans. Each case features migration patterns that are changing--or, in the case of the white marbled butterfly, which have been changed by deliberate human intervention. And in each case, we are observing changes with outcomes still uncertain over the longer term.

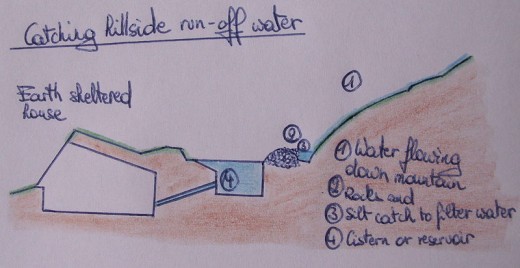

“Feast or Famine” shifts decisively to the human, examining the possibilities for the culture trait known as “agriculture.” Centered around the “possibilist” Ben Falk, who is building rice paddies on his Vermont homestead, the chapter discusses Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), soil depletion, genetic diversity for crop species, and water management.

No doubt is left as to the seriousness of the challenges faced by agriculture in general:

Already, crops are reaching climate thresholds. . . For instance, corn and soybeans are two of the four largest sources of calories in the world, of which the United States produces 41 and 38 percent respectively. . . . researchers found that at 84 degrees Fahrenheit (29 degrees Celsius), corn yields were significantly reduced. Similar trends were found for soy and cotton. . .

Over the next several decades, temperate areas of the globe will experience an additional 3-5 degrees Fahrenheit (1-2 degrees Celsius) increase, and tropical areas will increase between 4-7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5-3 degrees Celsius). “The coolest growing season of the future will be hotter than the warmest growing season of the past,” writes anthropologist Cary Fowler.

“Our Newest and Oldest Energy” considers the prospects for solar energy. It is not, however, a theoretical treatise, but a report from the energy front. In the Seidl basement is a standard water heater:

Five feet tall and cylindrical, it stands soldier-like in the corner, a testament to the modern conveniences that Americans have come to expect.

What is unusual about my basement is the bank of batteries to the left of the heater. There are twelve of them. At three feet tall and one hundred pounds each, they take up the majority of the room’s small footprint. Above the battery bank and connected to it is a piece of electronics the size of a toaster oven. Red and green lights blink from tiny bulbs, and a digital display flashes a number. This is the inverter, a device that transforms the electrical current from the batteries into one that appliances can plug into. A charge controller with a gray ready-grip handle is within reach to shut everything off, just in case.

As Dr. Seidl observes, in the early years of twentieth century America, the water heater would have been just as unexpected in a typical basement as the battery bank—though perhaps a little easier for the inhabitants to understand. The point of the batteries for the Seidl family is that the family is completely off the electrical grid: all the electric power that they use is produced on the property. There is solar photovoltaic:

My house’s roof and south-facing walls are completely covered in solar panels. They have been mounted to collect the rays of the sun once it rises above the maple, birch, and hemlock forest that founds our property to the south. The arrays look like mirrored sails and cast a silvery iridescent color not unlike that given off by calm water on a summer’s day. The aesthetic is beautiful and functional and the panels convey an unmistakable message: a modest American home can power itself with energy from its roof.

This is supplememented with a small wind turbine:

The machine was quiet, less than 1 kilowatt in size, and its light pine blades were hardly three feet across. . . Winds are strongest in the winter and early spring, the same seasons that solar gain is at its minimum. One blustery evening, I check the meter. The diode is green and the system is charging. We are converting something our neighbors complain about—high winds on a winter night—to a tangible good, a valuable commodity.

Still, the depth of winter can bring times where these renewable energy sources are not enough; the Seidl house, though taking reasonable steps to conserve energy, does not do so by self-denial. (Dr. Siedl’s list of electric tools, toys and appliances found in her house occupies more than a page, and is probably pretty typical for a contemporary American household with two children.)

For those lean times for renewable energy, the Seidls have an 8-kilowatt gas generator. It is an unfortunate but, for now, necessary compromise:

If cost were not limiting, we’d buy twice the number of batteries; we’d double our solar array and put a 3-kilowatt turbine on our wind tower. This upgrade would ensure the final silencing of the generator, but it would cost tens of thousands of dollars beyond what we have already spent. Plus, in July, we’d be so flush with power that by 10:00 a.m. the system would shut down.

That reality at least lets Dr. Seidl highlight the importance of energy storage to the renewables revolution—she dreams of a cobalt-catalyzed electrolysis process that would “allow us to generate hydrogen in July to feed a hydrogen fuel cell—an advanced technology whose only emission is water—in January.” (Such a system is under development by Daniel Nocera, of M.I.T.)

“Localizing Home” gives us examples of how to build sustainable homes and communities—and, in the case of Greenburg, Kansas, flattened by a tornado on May 4, 2007, how to re-build a more sustainable community. One attractive example is the Willow School in Gladstone, New Jersey:

Constructed wetlands and outdoor gardens receive wastewater and runoff, ecologically treating polluted water. Permeable paving stones and parking lots, living roofs and bioswales (meandering ditches that retain storm water long enough to trap pollutants and silt in their vegetated slopes ) all contribute to “fitting” the Willow School into its environment. Aware that the landscape used to be a forest before the school purchased it, the design actively encourages the land to become a forest again. In this way it will achieve its highest ecological potential: a living watershed able to store carbon, filter water, release oxygen, and house biodiversity.

“Self-Reliance 2.0” looks at appropriate technology new and old, the “culture of complicity” which virtually forces even climate activists to make use of carbon-intensive technologies at times, and the complex relationship between self-sufficiency and interconnectedness:

According to [Thomas] Princen, people are connecting the limits of the planet to personal behavior, limiting ourselves in the quotidian aspects of our lives. . .[it] is not without difficulties. . . [yet] people find that not consuming also has its benefits. . . In effect we are being asked to control our quest for more.

“The Pragmatism of Adaptation” opens by juxtaposing ideas. First is the intellectual pragmatism advocated following the American Civil War by Oliver Wendell Holmes and William Dewey, later furthered by John Dewey and Jane Addams, and ultimately joining with environmental ethics in the tradition of Rachel Carson to form a new and distinctive “environmental pragmatism.”

Second is Glenn Albrecht’s coinage of the term solastalgia:

When there is environmental disruption and a community like the Canadian Inuit experience the ice melting and the their way of life ending, they experience solastalgia. When subsistence farmers in Ghana can no longer predict the planting season because of radical changes in rainfall, they mourn for what their lands used to be like. They experience solastalgia.

In a word, solastalgia is the pain “people have when their home places no longer feel like their own.”

What is the relationship between these two sets of ideas? Dr. Seidl answers that implicit question with a lovely history:

One day a third-grade teacher asked me if her class could visit my house. They were studying electricity and wanted to see a solar home. A couple of weeks later, four carloads of third graders, parent chaperones, and teachers sat cross-legged in my living room. They pushed the toaster, played a CD, turned on a lamp, and read out the watt hours consumed for each appliance. They stood around the batteries in the basement and asked where they came from. They looked up at the laundraire (a device allowing convenient indoor laundry drying) and found it “cool.”

This visit inspired Dr. Seidl and three other parents to raise money to install a solar system at the elementary school. It took two years to raise $20,000, and to install two arrays at the edge of the playground. They planted a vegetable garden around it, and developed two grades worth of curriculum around the science. It could be dismissed as tokenism by cynics: “The amount of electricity produced by the 4 kilowatts of solar at our school is minimal compared to the amount it consumes in a year; less than 5 percent.”

But its purpose, appropriately enough for a school, is primarily educational. And the story doesn’t end there. Just as the solar home inspired the solar school, the solar elementary school inspired the solar middle school:

In 2011 the middle school, with a population of five hundred children from four towns, will install 200 kilowatts of solar energy on its flat roof. . . the array will be one of the largest in Vermont.

Dr. Seidl sees this environmentally pragmatic response as an answer to solastalgia: we mourn, but we continue to work, and to believe in life, and to strive to further its continuance and flourishing. She also sees it as paradigm:

The signals of ecological constraint are all around us, yet individual and civic responses to environmental degradation are also emerging. I recognize them and I am a part of them. I predict that in time they will coalesce into a social and adaptive response to climate change. This will be a genetic-like change that will spread through us to our offspring and become fixed in our culture.

Think for a moment of ideas that initially were met with resistance but later became mundane. In the early days of electrification, people recoiled at the idea of a lightning-like current (AC or DC) in the walls of their homes. When automobiles were first introduced, people assumed they would never travel more than fifteen miles per hour; otherwise they would scare the horses! But education and implementation eventually led to acceptance of technologies that are now commonplace. In the same way, practices that may have once gone unquestioned—the use of aerosol spray cans containing fluorocarbon, littering—have become anathema, jarring our ethical sensibilities. Now the same is happening with were and what we purchase.

No doubt some readers will reflexively reject this perception as that of a Pollyanna. With species extinction already surging, large-scale political responses spotty at best, political pushback from well-funded interest groups who gain from prolongation of the status quo, Arctic sea ice vanishing, and--more immediately threatening--numerous current examples of intensified flooding and drought, is it realistic to think that a few individuals and groups building sustainable buildings, striving for more localized economies and practicing DIY water management can possibly save the planet--or at least, humanity's place upon it?

But recall that Dr. Seidl is no romanticist: her everyday life is intimately tied up with the exigencies of the Age of Warming. Undoubtedly it is easier to believe in a change when one has already embraced it one’s self. In that sense, Finding Higher Ground is an invitation, a beautifully-written “come on in, the water’s fine!” As the old adage has it, “be the change you wish to see.”

Let’s give the last word to Dr. Seidl herself:

But higher ground also lies in territory beyond these pragmatic actions. It is in our determination to care about what we love, to protect life that is threatened, to grieve for what is lost, and to believe we can endure the Age of Warming. The biological and cultural environments that we have depended on in the past will undoubtedly change. But the adaptations we bring into existence will be the very makings of our persistence.

This Hub is part of a series. Read the previous Hub:

- "The Long Thaw": A Summary Review

One of the best books on the science of climate. University of Chicago professor David Archer explains Earth's climate, proceeding systematically from shorter timescales--the present and immediate human future--to longer ones. Get the gist!

Other Hubs by Doc Snow

- "Green Fascism": Let The Facts Speak

Activists, researchers and ordinary people expressing their concern about climate change have been called "eco-Nazis" or "green Fascists." Yet it is they who have been vilified, suppressed and threatened. Read this largely unreported story. - Pet Doors For Dogs Or Cats: How (Not) To Install Them

If you have an animal companion in your home, it can do wonders for the satisfaction of all concerned to allow free access to the outdoors. It can be easier (and less expensive) than you might think. Read how--and how NOT!--to do it here! - Sudoku Sherlock-Style: Getting To N-1

Sudoku is a lot of fun. But though the rules are easy to grasp, some folks are intimidated by the strategy. Here's an easy approach for them--and for those who just want to get a little faster at Sudoku solving. - Understand Chords: Beyond Seventh Chords To Chord Extensions--Ninths, Elevenths And Thirteenths (Pa

Ninth-, eleventh-, and thirteenth-chords are 'hip.' But just how do you create and use them? And what do they actually sound like? Read about them--and hear them!--here.